Article / Research Article

1The Human Relations Institute and Clinics, DMCC

2Meadowspath, Washington

3Heriot-Watt University, Knowledge Park, Dubai.

Thoraiya Kanafani,

The Human Relations Institute and Clinics, DMCC, Dubai.

23 January 2025 ; 12 February 2025

This study explores the stigma, beliefs, and behaviors toward mental health among Arabs and Subcontinent Asians, regions where mental health issues are prevalent yet underreported due to cultural and social stigmas. We surveyed 578 participants from these regions to understand their attitudes towards mental health and help-seeking behaviors, considering variables such as gender, age, and previous mental health service use. Our findings reveal significant predictors of mental health attitudes: prior mental health service history, age, and gender notably influenced personal stigma and psychological openness, while ethnicity and place of residence did not. Males exhibited higher personal stigma and indifference to stigma compared to females, who were more open to seeking emotional support. Older adults showed a greater propensity for help-seeking but lower psychological openness. Interventions for reducing stigma and increasing access to mental health services are discussed.

Psychological disorders have become an immense global burden, economically and socially, with over 500 million affected by anxiety or depression worldwide (Dattani, et al., 2021) and can cause high rates of morbidity and mortality. Despite this, few people suffering with a mental illness seek help, or only do so after a significant delay (Henderson, et al., 2013). Indeed, it is widely accepted that early intervention, and seeking help from a mental health professional, is crucial to reducing the burden of mental health difficulties. Moreover, the benefits to seeking help at an early stage include reducing social and personal financial costs associated with the mental illness, preventing future relapses, and improving overall quality of life.

Post-Covid 19, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated a 25% increase in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression. In the Arab world, it is estimated that 17.7% of the population suffers from depression and the prevalence of other mental health disorders such as anxiety, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress, and substance abuse is estimated between 15.6% to 35.5%, with higher rates due to war and conflict (Ibrahim, 2021). Moreover, Naveed and colleagues (2020) reported the highest prevalence of common mental disorders globally in countries of the Asian Subcontinent. Although the prevalence of disorders rose globally, there is a higher proportion (~80%) among people who reside in low- and middle-income countries. Indeed, in over 135 studies conducted in Asian Subcontinent countries, the total prevalence of depressive symptoms indicated an average prevalence rate of 26.4% among 173,449 participants (Naveed et al., 2020). In another study, the Asian Subcontinent sample had a 24.5% lifetime rate of any DSM-IV mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder (Lee et al., 2015).

Although mental health continues to negatively affect people within these regions, mental health stigma continues to negatively impact the likelihood of seeking treatment.

Goffman (1963) coined the term stigma which refers to a set of negative attitudes and beliefs that motivate people to fear, reject, avoid, and discriminate against people with mental health difficulties (Corrigan & Penn, 1999). Research around stigma investigates three different types: Public, private and structural. Public stigma refers to the negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that a society or community holds about a particular group of individuals (De Freitas et al., 2018). Private stigma is the internalized form of public stigma where the individual believes in the negative labels assigned to them by their society (Mohammadzadeh et al., 2020). Structural stigma refers to the societal-level and institutional practices and cultural norms which limit stigmatized populations’ well-being and opportunities (Hatzenbuehler & Link, 2015).

Mental health stigma significantly widens the service and treatment gaps for individuals who could benefit from mental health services. Common by-products of stigma are shame and low self-esteem, which can further exacerbate mental health difficulties. Individuals experiencing mental health difficulties not only have to battle their inner conflicts and the burden of dealing with them but must also cope with societal stigmatization of their difficulties (Hatzenbuehler & Link, 2015). Moreover, public stigma has been associated with poor compliance and utilization of mental health services, prognosis, and decreased engagement in services (Gearing et al., 2013).

Sewilam and colleagues (2015) have shown that stigma towards people suffering with mental health difficulties is widespread amongst Arabs in the Middle East. Furthermore, studies on South Asian students found a negative association between personal stigma and help seeking behaviors, suggesting that as personal stigma increases, the likelihood of engaging in help-seeking behaviors decrease. Studies have shown that mental health stigma toward seeking psychological help is negatively associated with a willingness to seek counselling (Kim & Park, 2009). Previous findings have also shown that the more knowledge people have of mental health disorders, the more stigma exists, which manifests in low rates of seeking psychiatric or psychological help, reduced tolerance, and acceptance towards those who have mental health difficulties (Abi Doumit et al., 2019).

In the study reported here, we investigated stigma, beliefs, and behaviors towards seeking mental health support in both the Arab and Asia Subcontinent regions. The Arab countries of interest include Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Yemen, and Oman. These countries are typically high in collectivism, where self-concept is derived from belonging to a group or family (Gearing et al., 2013) and share the same traditions, values, language and beliefs (Dardas & Simmons, 2015). Moreover, symptoms of mental health difficulties in the Arab world are usually attributed to sociocultural and deep religious beliefs, and seen to be a punishment by God, the evil eye, Jinn, demonic possession, or black magic, which often leads to the visitation of a religious or spiritual healer for guidance and treatment (Rayan & Fawaz, 2018). Even though college/university years are typically a period of increased psychological distress, numerous studies have shown that Arab university students are reluctant to seek counseling services due to cultural barriers (Al-Rowaie, 2001), which emphasize speaking to family members or friends or a religious leader. The Asian Subcontinent region included Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. As with the Arab countries, Asian Subcontinent countries are similarly high in collectivism and traditional Asian Subcontinent countries follow cultural values that may directly influence mental health seeking behaviors such as social conformity, public appearance and behavior expectations, and discomfort with self-disclosure outside of the immediate family (Arora et al., 2016). In Asian Subcontinent countries, mental health stigma presents itself through devaluing, disgracing, and disfavoring individuals experiencing mental health difficulties (Mudunna et al., 2022). In such countries, mental health difficulties are also attributed to sociocultural and religious beliefs, namely as a punishment from God, a consequence of bad deeds in a previous life (consequence of karma), ‘bad genes’, or influence of evil spirits (Arora et al., 2016).

For both widespread collectivistic regions, there is a large emphasis on familial relations and group-oriented identity. Since people from collectivist cultures attribute a person’s actions and behaviors as a reflection of their family, publicly admitting to experiencing mental health difficulties can bring shame and stigma upon one’s family. This family stigma has been shown to lead to feelings of shame, a reluctance to seek psychological or psychiatric assistance, self-blame, loss of social standing, and reduced marriage prospects.

Although the experience of stress is universal, many studies have demonstrated that men and women cope differently to perceived stress (Graves et al., 2021). With coping defined by Folkman and Lazarus (1980) as a person’s efforts to use cognitive and behavioral strategies to manage pressures and emotions in response to stress. Coping is essential to our understanding of how people adapt and adjust in the face of adversity. Not only do males and females cope with stress differently (Graves et al.), research has shown that there are gender differences in emotional reactivity (Deng, et al., 2016) with women reporting higher levels of arousal for sadness than men. It is important to note that in the same study by Deng and colleagues, it was found that men and women have the same emotional experience, however they differed in how they expressed their emotions.

Researchers have divided coping strategies into categories such as problem-focused versus emotion-focused; adaptive versus maladaptive; active versus passive. For the purposes of this study, we will refer to problem-focused coping in line with the literature. Problem-focused coping refers to finding practical ways to manage stressful situations. It also entails an individual making active efforts to modify or eliminate sources of stress and tackling problems “head on”. In contrast, emotion-focused coping includes all the regulative efforts to reduce the emotional consequences of stressful situations, such as finding short-term distractions, seeking social/emotional support, venting, and cognitive restructuring. In summary, the objective of problem-focused coping is to manage or change the source of a problem whereas emotion-focused coping aims to regulate one’s emotional response to a problem (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Although there is no specific right or wrong way of coping, some strategies are said to be more (mal)adaptive than others. For instance, problem-focused active coping has been associated with higher self-esteem and wellbeing (Barendregt et al., 2015). Numerous studies have shown that females tend to use emotion-focused coping (Graves et al., 2021) which suggests strong gender differences in the use of coping strategies.

Since females are more likely to engage in emotion-focused coping it may come as no surprise that several studies have further shown that women are more inclined to seek help for psychological-related issues (Lidon, et al., 2018). For example, in a large cross-sectional study (Oliver, et al., 2005) conducted in the UK males with or without mental problems preferred not to seek any form of help, from either lay sources or professionals. No explanation was provided for these gender differences, and it would have been helpful to understand the personal beliefs underlying help-seeking behavior in their participants. Accordingly, the study reported here aims to explore attitudes and beliefs surrounding help-seeking behavior among men and women with the hopes of narrowing the gap in the literature.

Although it is not uncommon for older adults to experience mental health challenges that may require help or assistance as they age, they are less likely to seek help for their physical or mental health difficulties (Mackenzie et al., 2008). In a recent systematic review, Teo and colleagues (2022) identified potential barriers that prevent older adults from seeking help including the negative perceptions of, and relationships with, healthcare providers as well as perceived threats to independence. Additionally, cultural beliefs, immigration, and language were found to be additional barriers among minority ethnic older adults. It is important to highlight that most of the studies that were conducted in Europe and North America, which come with their own limitations for extrapolation to other populations. In support of the previous findings, another study (Melendez et al., 2012) found that elderly adults, compared to middle-aged adults, showed a significant decline in the use of problem-focused coping and a tendency rely on social support.

In contrast, a relatively recent study by Mackenzie and colleagues (2019) explored public and self-stigma of seeking help, and attitudes toward seeking help in a sample of 5,712 Canadians, the results of which indicated that older adults had the lowest levels of stigma and the most positive-seeking attitudes. This may be due to the Canadian public healthcare system being readily accessible, which may encourage people to seek help. Additionally, it may be that there is no stigma associated with seeking help for physical or mental health due to widespread awareness and knowledge that is instilled at a young age; therefore, normalizing the idea around help-seeking behaviors and reducing feelings of inadequacy and shame.

Accordingly, the study reported here examines the stigma associated with mental health and mental health treatment amongst Arab and Asian Subcontinent countries. Many studies have looked at the effects that mental health stigma has on the population of individuals and their families that are affected by mental health difficulties (Abi Doumit et al., 2019). The social constructivist theory is useful to explain how a person’s perceptions, beliefs, and values are influenced by their cultural norms which will shape their perceptions of mental health and the methods to cope with mental health difficulties (Leung et al., 2011). Our aim is to understand more about these attitudes and beliefs and their effects on professional help seeking behavior. Improving this understanding may guide professionals on how to address awareness, increasing positive perceptions of mental health, and providing important resources to help develop proper mental health literacy awareness campaigns and educational programs.

An examination of the wider literature revealed that while attitudes toward help-seeking has been widely studied in Western populations, less attention has been given to Arabs and Subcontinent Asians living in the Middle East and Subcontinent Asia. This study, therefore, aims to investigate differences between Arabs and Subcontinent Asians in their attitude towards mental health and help-seeking behaviors. The study further aims to examine the difference between male and female participants’ attitudes towards mental health and help seeking behavior. Lastly this study aims to assess any association between age and attitude towards mental health and help seeking behavior.

H1: There will be similarities in attitude towards mental health and help seeking behavior between Arabs and Subcontinent Asians due to their shared collectivistic cultures.

H2: There will be significant difference between male and female participants in their attitude towards mental health and help seeking behavior.

H3: The association between age and attitude towards mental health and help seeking behavior will be significant.

Participants

Five hundred and seventy-eight participants took part in this study (155 males, 424 females and 4 gender non-conforming) with an age range of 18-78 (mean 35.6). All participants ethnically identified with a country included in the study’s definition of Arab or Asian Subcontinent countries and held permanent residency in any of those countries. Permanent residency was defined as living for at least 6 months of a year in one country. Participants were fluent in English and no monetary forms of compensation were provided to research volunteers.

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the School of Social Sciences Ethics Committee at a University, Dubai. Data collection was through convenience sampling. Participants were recruited by posting survey links on the researchers’ social media (e.g., Instagram, Facebook, Twitter) and all participants were asked to sign an online informed consent form. Data was collected through a structured anonymous online survey consisting of study specific questions, and widely used standardized questionnaires about the stigma associated with mental health and help seeking behavior.

Participants were asked to fill out demographic information regarding their age, gender, ethnicity, country of residence, years of residence, marital status, educational background, employment status, previous experience with mental health treatment, ethnically relevant beliefs about mental health, among other basic information.

Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services (IASMHS) (Mackenzie et al., 2004)

The IASMHS is a 24-item questionnaire that measures attitudes toward seeking mental health support. The IASMHS has been validated in many different countries with an overall validity ranging from 0.84-0.87 (Bras, et al., 2022). The IASMHS has three subscales: Psychological openness, help-seeking propensity, and indifference to stigma. Items are measured using a five-point Likert-scale ranging from 0 (disagree) to 4 (agree). Each subscale contains eight items. A sample item from the Indifference to Stigma subscale is “having been mentally ill carries with it a burden of shame”.

Perceived public stigma and personal stigma was measured using an adaptated Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Scale (D-D) (Link, 1987; Link et al., 1989) is a 12-item questionnaire that measures perceptions of stigma. The scale uses a six-point Likert-scale ranging from 0 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) and has shown a high internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = .89). An example of one of these three items is “I would think less of a person who has received mental health treatment”.

This study assessed the potential impact of demographic variables on individuals’ attitudes toward mental health. Specifically, the focus areas encompassed help-seeking personality, indifference to stigma, psychological openness, personal stigma, and social stigma.

To examine the interrelationships among various attitudes toward mental health, a Pearson correlation test was used. The findings revealed a negative correlation between help-seeking personality and indifference to stigma, personal stigma, and psychological openness. Conversely, indifference to stigma showed a positive correlation with psychological openness, personal stigma, and social stigma. Furthermore, psychological openness exhibited a positive correlation with personal stigma, while social stigma was positively correlated with personal stigma.

CS does not derive from depressive motivations per se, but from psychodynamics linked to anger, hatred, frustration, envy and revenge. It is often incited by the desire to punish, torture, hurt, or take revenge on others.The mediating psychodynamics of DS and BS are more related to conflicts, desires, or self-referential interests of self-recrimination, self-flagellation and punishment.

| Indifference to Stigma | Psychological Openness | Social Stigma | Personal Stigma | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Help Seeking Propensity | r | -.212** | -.196** | -.090* | |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.030 | ||

| Indifference to Stigma | r | .468** | .212** | .246** | |

| Indifference to Stigma | p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Psychological Openness | r | .215** | |||

| p | 0.000 | ||||

| Social Stigma | r | .121** | |||

| Social Stigma | p | 0.004 |

Table 1: Mental Health Attitude Interrelationships

This study employed multiple regression analysis to explore the predictive influence of several variables on participants’ attitudes toward mental health, including prior mental health services history, age, gender, ethnicity, and place of residency. The results indicated that prior mental health services history, age, and gender served as predictors significantly impacting Personal Stigma and Psychological Openness. Moreover, prior mental health services usage and age emerged as predictors of help-seeking behaviour. Gender, however, emerged as a sole predictor for Indifference to Stigma. Interestingly, none of these factors exhibited predictive capacity for social stigma. Furthermore, neither ethnicity nor place of residence demonstrated predictive capabilities for any of the examined mental health attitudes.

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Psychological Openness | Standardized Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t | Sig | ||

| Psychological Openness | Prior mental health services | -3.40 | 0.44 | -0.30 | -7.64 | 0.000 |

| Age | -0.05 | 0.02 | -0.09 | -2.22 | 0.027 | |

| Gender | 1.88 | 0.49 | 0.15 | 3.81 | 0.000 | |

| Help Seeking Propensity | Prior mental health services | 2.23 | 0.45 | 0.20 | 4.89 | 0.000 |

| Personal Stigma | Age | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 5.72 | 0.000 |

| Indifference to Stigma | Gender | 1.70 | 0.52 | 0.14 | 3.28 | 0.001 |

| Personal Stigma | Prior mental health services | -0.09 | 0.04 | -0.09 | -2.28 | 0.023 |

| Personal Stigma | Age | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 2.60 | 0.009 |

| Personal Stigma | Gender | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 2.49 | 0.013 |

Table 2: Mental Health Attitudes and Personal Attitudes

Following the regression analysis, a series of follow-up tests were undertaken to delve deeper into the impact of the predictor’s factors for each mental health attitude.

Multiple regression analysis showed prior mental health services history, gender, and age predict personal stigma. A two-way independent ANOVA was conducted that examined the effect of prior mental health services history and gender on Personal Stigma. There was a significant main effect of prior mental health services history on Personal Stigma F(1, 574) = 4.47, p = .01, η2p=.01, showing the mean score of Personal Stigma in those without prior mental health services history was higher (M = 5.24, SD = .58) than those with prior mental health services history (M = 5.14, SD = .39). There was also a significant main effect of Gender on Personal Stigma F(1, 574) = 6.29, p = .012, , η2p=.01, with the mean score of Personal Stigma higher in males (M = 5.26, SD = .62) compared to females (M = 5.15, SD = .42). However, there was no statistically significant interaction between the effects of prior mental health services history and gender on Personal Stigma, F(1, 574) = .01, p =.91 > .05, η2p=.00. For further investigation, a simple main effects analysis showed that females without prior mental health services history (M = 5.21, SD = .52) scored significantly higher in Personal Stigma than females with prior mental health services history (M = 5.10, SD =4.32), (p = .033), but there were no differences among males with and without prior mental health services history p = .24.

Additionally, males with prior mental health services history (M = 5.26, SD = .63) scored higher than females with prior mental health services history (M = 5.15, SD = .42), in Personal Stigma p = .049. However, there was no significant difference between males and females who did not have prior mental health services history p = .11.

Furthermore, a Pearson correlation was conducted to explore the relationship between Personal Stigma and age, revealing a significant yet weak positive association (r (578) = 0.10, p = .02). This finding suggests that an increase in age is associated with an increase in Personal Stigma.

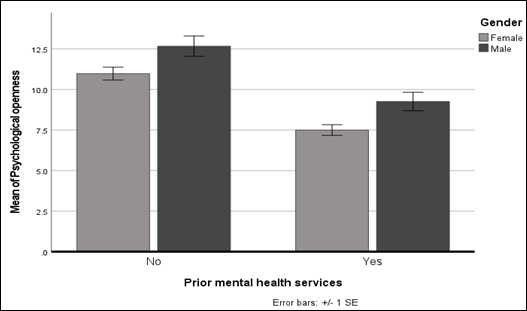

Multiple regression analysis showed prior mental health services history, gender, and age predict Psychological Openness. A two-way independent ANOVA was conducted that examined the effect of prior mental health services history and gender on Psychological Openness. There was a significant main effect of prior mental health services history on Psychological Openness F(1, 574) = 48.38, p < .001, η2p=.08, showing the mean score of Psychological Openness in those without prior mental health services history was higher (M = 11.46, SD = 5.45) than those with prior mental health services history (M = 7.95, SD = 5.16). There was also a significant main effect of gender on Psychological Openness F(1, 574) = 12.17, p = .02, , η2p=.02, showing the mean score of Psychological Openness was higher in males (M = 10.80, SD = 5.98) compared with females (M = 8.94, SD = 5.32). However, there was not a statistically significant interaction between the effects of prior mental health services history and gender on Psychological Openness, F(1, 574) = .00, p =.95 > .05, η2p=.00.

For further investigation, a simple main effect analysis was conducted, and the results showed, females without prior mental health services history (M = 10.98, SD = 5.16) scored significantly higher than females with prior mental health services history (M = 7.50, SD = 4.95) in Psychological Openness, p< .001. The same pattern also was seen among males, males who had no prior mental health services history (M = 12.67, SD = 5.97) scored significantly higher on Psychological Openness compared males with prior mental health services history (M = 9.26, SD = 5.56), p<.001.

Additionally, males without prior mental health services history (M = 12.67, SD = 5.97) scored significantly higher than females without prior mental health services history (M = 9.26, SD = 5.56) on Psychological Openness, p = .023. Similar pattern also was seen in participants who had prior mental health services history. Males with prior mental health services history (M = 9.26, SD = 5.56) scored significantly higher than females without prior mental health services history (M = 7.50, SD = 4.95), p = .008.

Figure 1: Prior experience with mental health services

A Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between Psychological Openness and age. The correlation coefficient between the two variables showed a significant negative weak association r (578) = -0.10, p = .018, indicating increasing age is associated with decreasing Psychological Openness.

Multiple regression analysis showed only gender predicts indifference to stigma.

An independent t-test was conducted to compare males and females scores in indifference to stigma. The results revealed a significant difference between the two groups, considering Equal variances not assumed (p = .001), t(238.63) = 2.84, p = .005, showing males (M = 7.85, SD = 6.15) scored higher compared to females (M = 6.27, SD = 5.18).

Multiple regression analysis showed only prior mental health services history predicts help seeking personality. To compare the mean scores of help-seeking personality between those with prior mental health services history and those without, an independent t-test was conducted. The results revealed a significant difference between the two groups (p = .011), t(475.74) = 4.65, p < .001, showing those with prior mental health services history (M = 29.90, SD = 5.09) scored higher than those without prior mental health services history (M = 27.71, SD = 5.96). Additionally, a Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between help seeking personality and age. The correlation coefficient between the two variables showed a significant positive moderate association r(578) = .22, p<.001, indicating increase in age is associated with and increase in help seeking personality scores.

The purpose of our study was to examine the stigma associated with mental health and mental health treatment amongst Arab and Asian Subcontinent countries. Our aim was to understand how attitudes and beliefs towards mental health impacts professional help seeking behavior. For our first hypotheses, we predicted that there would not be any significant differences in attitude toward mental health and help seeking behavior between Arabs and Subcontinent Asians due to their shared collectivistic cultures. Indeed, it was found that neither ethnicity nor place of residence predicted any of the examined mental health attitudes (e.g. help-seeking behaviors, personal stigma). This is likely because, although the participants came from geographically different areas, their strong shared cultural values of collectivism likely shaped their perceptions of mental health and the methods used to cope with mental health difficulties and self-disclosure outside of their immediate family (Arora et al., 2016).

The findings of our study revealed that individuals who had previously accessed mental health services were more willing to seek mental health support again in the future. Additionally, our findings indicated that those with a history of using mental health services scored lower on the Personal Stigma subscale compared to those who had not, suggesting that their openness and attitude, and even perhaps positive experience accessing mental health services, played a role in openness to help seeking behavior.

Another interpretation to these findings could be that individuals who accessed mental health services in the past had had a positive experience (i.e. found it useful) and thus were more likely or encouraged to seek support through such services in the future. One limitation in the current study is that we did not specifically explore which mental health service participants were more likely to seek such as psychiatrists, psychologists, family physicians, or alternative medicine practitioners. It may be worthwhile to explore this in future research.

Younger participants (ages X-Y) in comparison to older participants (ages X-Y) were more likely to seek mental health support as indicated by higher scores on the Help-Seeking behavior subscale. This finding is in line with previous findings (Melendez et al., 2012) that indicate older people are less likely to use problem-focused coping and a tendency to rely on social support rather than professional help.

Males in comparison to females had significantly higher scores on the Personal Stigma subscale, which suggests that they hold higher stigmatizing attitudes regarding mental health treatment. These findings are not surprising to say the least. In fact, they are consistent with many past studies (Mackenzie, et al., 2006) that indicate that men’s negative attitudes might contribute to their underutilization of mental health services.

Our findings showed significant differences between males and females on the indifference to stigma subscale, with males reporting higher scores on this subscale. This suggests that males in comparison to females are far more concerned about others finding out if they were receiving professional support for their mental health. Once again, this supports previous findings (Chatmon, 2020) but with data from previously underreported populations, i.e. the Arab and Asian Subcontinent region (Kanafani et al., 2023). One possible explanation to our findings is that females typically tend to use more emotion-focused coping strategies which include seeking emotional support and venting. Therefore, the idea of seeking support from a professional for mental health support is not necessarily shameful or regarded as “taboo” (Graves et al., 2021).

Moreover, the perceived stigma surrounding mental health by men partly explains their overall reluctance to seek treatment, although there is a clear and urgent need to bridge this gap since depression and suicide are ranked as one of the leading causes of death among men. To reduce the barrier of seeking mental health support particularly for men, it is suggested that more awareness campaigns and psychoeducation within various communities on a global scale would be helpful. For instance, November is known as men’s health awareness month. While it is important to raise awareness in November, we argue that we should be more vocal around men’s mental health and address it more openly and frequently. Doing so would help promote healthy behaviors, normalize mental health struggles, reduce the risk of severe mental illness, and improve overall quality of life.

Additionally, our findings showed a positive moderate correlation between age and help-seeking personality. This suggests that older age is associated with an increase in help-seeking personality. This finding supports past studies (Mackenzie, et al., 2006) that have shown positive attitudes towards help-seeking. However, we also found a negative correlation between age and psychological openness, which suggests that aging is associated with decreased psychological openness. In a study by Segal and colleagues (2005), it was found that older adults were more likely to view mental illness as embarrassing and attributed the cause to having poor social skills. Taken together, our findings suggest that while older adults reportedly believe they are willing to seek mental health support, they also find it difficult to openly admit that that may be experiencing mental health struggles which in turn could play a role in their underutilization of mental health services. We argue that normalizing the existence of mental health difficulties at any age and providing more awareness through means accessible to an older population would be helpful in reducing the stigma surrounding mental health. For instance, while many psychotherapists use social media platforms to provide psychoeducation, this may be inaccessible to older adults therefore it is suggested that there be more targeted and accessible information specifically for older adults (e.g. commercials on the television, pamphlets at the primary physician).

There are several factors that may explain the current findings, beyond what was studied. These include a lack of knowledge of mental health symptoms, fear of stigmatization, and economic concerns. For example, mental health services are primarily dominated by the private sector in Arab and Asian countries which may contribute to the reluctance of many people to seek professional help.

- Dattani, S., Rodés-Guirao, L., Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2021). “Mental Heath”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

- Henderson, C., Evans-Lacko, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 777-80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2012.301056

- Ibrahim, N. K. (2021). Epidemiology of Mental Health Problems in the Middle East. Handbook of Healthcare in the Arab World, 133-149. https://10.1007/978-3-319-74365_12-1

- Naveed, S., Waqas, A., Chaudhary, A. M. D., Kumar, S., Abbas, N., Amin, R., and Saleem, S. (2020). Prevalence of common mental disorders in South Asia: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 573150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.573150

- Lee, S. Y., Martins, S. S., & Lee, H. B. (2015). Mental disorders and mental health service use across Asian American subethnic groups in the United States. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(2), 153-160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9749-0

- Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes in the management of spoiled identity, Englewood Cliffs, NJ : Prentice-Hall. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1018094

- Corrigan, P.W., & Penn, D.L. (1999). Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. American Psychologist, 54(9), 765-776. DOI:https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.765

- DeFreitas, S. C., Crone, T., DeLeon, M., & Ajayi, A. (2018). Perceived and personal mental health stigma in Latino and African American college students, Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00049

- Mohammadzadeh, M., Awang, H., & Mirzaei, F. (2020). Mental health stigma among Middle Eastern adolescents: A protocol for a systematic review. Journal of Psychiatry Mental Health Nurse, 27(6), 829-837. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12627

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Link, B. G. (2014). Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc Sci Med, 103, 1-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.017

- Gearing, R. E., MacKenzie, M. J., Ibrahim, R. W., Brewer, K. B., Batayneh, J. S., & Schwalbe, C. S. (2014). Stigma and mental health treatment of adolescents with depression in Jordan. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(1), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9756-1

- Sewilam, A. M., Watson, A. M., Kassem, A. M., Clifton, S., McDonald, M. C., Lipski, R., Deshpande, S., Mansour, H., & Nimgaonkar, V. L. (2015). Suggested avenues to reduce the stigma of mental illness in the Middle East. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(2), 111-120. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014537234

- Kim, B. S. & Park, I. J. (2009). Testing a multiple mediation model of Asian American college students’ willingness to see a counselor. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(3), 295-302. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014396

- Abi Doumit, C., Haddad, C., Sacre, H., Salameh, P., Akel, M., Obeid, S., Akiki. M., Mattar, E., Hilal, N., Hallit, S., & Soufia, M. (2019). Knowledge, attitude and behaviors towards patients with mental illness: Results from a national Lebanese study, PLOS ONE, 14(9), e0222172. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222172

- Dardas, L. A., & Simmons, L. A. (2015). The stigma of mental illness in Arab families: A concept analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(9), 668-679. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12237

- Rayan, A. & Fawaz, M. (2018). Cultural misconceptions and public stigma against mental illness among Lebanese university students. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 54(2), 258-265. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12232

- Al-Rowaie, O. (2001). Predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help among Kuwait University students. Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/items/0a92b083-f367-4fb2-b18f-c9c3b77cda94/full

- Arora, P. G., Metz, K., & Carlson, C. I. (2016). Attitudes toward professional psychological help seeking in South Asian students: Role of stigma and gender. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(4), 236. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12053

- Mudunna, C., Antoniades, J., Tran, T., & Fisher, J. (2022). Factors influencing the attitudes of young Sri Lankan-Australians towards seeking mental healthcare: A national online survey. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 546. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12842-5

- Graves, B. S., Hall, M. E., Dias-Karch, C., Haischer, M. H., & Apter, C. (2021). Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS One, 16(8), e0255634. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255634

- Folkman S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(3), 219–239. DOI: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/2136617

- Deng, Y., Chang, L., Yang, M., Huo, M., & Zhou, R. (2016). Gender Differences in Emotional Response: Inconsistency between Experience and Expressivity. PLoS One, 11(6), e0158666. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158666

- Lazarus R. S., & Folkman S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer. https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Stress_Appraisal_and_Coping.html?id=i-ySQQuUpr8C&redir_esc=y

- Barendregt, C. S., Van der Laan, A. M., Bongers, I. L., & Van Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2015). Adolescents in secure residential care: the role of active and passive coping on general well-being and self-esteem. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(7), 845–854. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0629-5

- Oliver, M., Pearson, N., Coe, N., & Gunnell, D. (2005). Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(4), 297-301. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.4.297

- Mackenzie C. S., Scott T., Mather A., & Sareen J. (2008). Older adults’ help-seeking attitudes and treatment beliefs concerning mental health problems. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 1010–1019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/jgp.0b013e31818cd3be

- Teo, K., Churchill, R., Riadi, I., Kervin, L., Wister, A. V., & Cosco, T. D. (2022). Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(5), 1500–1510. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211067710

- Melendez, J., Mayordomo-Rodríguez, T., Sancho, P., & Tomás, J. M. (2012). Coping Strategies: Gender Differences and Development throughout Life Span. The Spanish journal of psychology, 15(3), 1089-98. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n3.39399

- Leung, P., Cheung, M., & Tsui, V. (2011). Asian Indians and depressive symptoms: Reframing mental health help-seeking behavior. International Social Work, 55(1), 53-70. DOI: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1177/0020872811407940

- Mackenzie, C. S., Knox, V. J., Gekoski, W. L., & Macaulay, H. L. (2004). An adaptation and extension of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol, 34(11), 2410–2435. DOI: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01984.x

- Bras, M., Cunha, A. M., Carmo, C., & Nunes, C. (2022). Inventory of attitudes toward seeking mental health services: Psychometric properties among adolescents. Social Sciences, 11(7), 284-296. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070284

- Link, B. G. (1987). Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An Assessment of the effects of expectations of rejections. American Sociological Review, 52(1), 96-112. DOI: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.2307/2095395

- Link, B. G., Cullen, F., Struening, E., Shrout, P., & Dohrenwend, B. (1989). A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 400-423. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2095613

- Mackenzie, C. S., Gekoski, W. L., & Knox, V. J. (2006). Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: the influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging Mental Health, 10(6), 574-82. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860600641200

- Chatmon B. N. (2020). Males and Mental Health Stigma. American Journal of Mens’ Health, 14(4), 1557988320949322. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988320949322

- Kanafani, T., Hassain, M., Correara, T., Yekani, H. A. K., & Sheen, M. (2023). The effectiveness of online vs face-to-face psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Neuroscience and Psychology, 5(2), 1-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47485/2693-2490.1069

- Segal, D. L., Coolidge, F. L., Mincic, M. S., & O’Riley, A. (2005). Beliefs about mental illness and willingness to seek help: a cross-sectional study. Aging Mental Health, 9(4), 363-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860500131047

- Aegisdottir, S. & Gerstein, L. H. (2009). Beliefs about psychological services (BAPS): Development and psychometric properties. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 22(2), 197-219. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09515070903157347

- Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 368–373. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1996-10056-001

- Youssef, J. & Deane, F.P. (2006). Factors influencing mental-health help-seeking in Arabic-speaking communities in Sydney, Australia. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 9(1), 43-66. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13674670512331335686.