Article / Review Article

Consultant, Clinica Esculapio, Ghezzano, Pisa, Italy.

Claudio Bencini, MD, FICS, FBHS,

Consultant, Clinica Esculapio, Ghezzano, Pisa,

Italy.

22 January 2026 ; 28 January 2026 ; 6 February 2026

Citation: Bencini, C. (2026). Parietal Inguinal Box Repair (PIBR) : An Anatomy-Driven Refinement of Anterior Mesh Hernioplasty. J Sur & Surgic Proce.,4(1):1-4. DOI : https://doi.org/10.47485/3069-8154.1026

Inguinal hernia repair has evolved from tissue-based reconstruction toward parietal reinforcement with prosthetic materials. Although mesh-based techniques have reduced recurrence rates, they have at times shifted attention away from functional anatomy toward standardized defect-oriented repairs.

The Parietal Inguinal Box Repair (PIBR) is presented as a full-length technical–conceptual evolution of anterior open hernia repair. The technique is based on a parietal, wall-centered interpretation of the inguinal region and focuses on reconstruction of the inguinal box as a functional three-dimensional compartment rather than on treatment of the peritoneal sac.

PIBR is performed through an open anterior approach according to tension-free principles. The hernia sac is reduced without dissection or resection. A tailored flat mesh is positioned anteriorly and stabilized through selective three-point fixation to the pubic tubercle, the pubic ramus (pectineal ligament), and the inguinal ligament.

By integrating classical anatomical principles with contemporary mesh-based surgery, PIBR represents an anatomy-driven refinement of anterior hernioplasty.

The history of inguinal hernia surgery closely reflects the progressive understanding of abdominal wall anatomy and function. Early operative strategies were grounded in descriptive anatomy and in the systematic surgical-anatomical interpretation of the inguinal region, providing the conceptual framework for anterior open repairs based on direct visualization and layered reconstruction (Skandalakis et al., 1995).

A decisive turning point occurred with the work of Bassini, who introduced a methodical and reproducible technique based on reconstruction of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. By suturing the internal oblique muscle, transversus abdominis muscle, and transversalis fascia to stable osteoligamentous landmarks, Bassini shifted surgical focus from the hernia sac itself to the integrity of the abdominal wall (Bassini, 1887; Bassini, 1890).

Subsequent anatomical insights progressively moved beyond the concept of isolated defects. The description of the myopectineal orifice as a unified area of parietal weakness clarified that inguinal and femoral hernias share a common anatomical substrate (Fruchaud, 1956). This functional interpretation laid the conceptual foundation for posterior and preperitoneal repairs, and it remains central to contemporary endoscopic approaches aimed at reinforcing the entire myopectineal region (Nyhus, 1995; Wantz, 1991).

The introduction of prosthetic materials marked another major step in the evolution of hernia surgery. Mesh-based, tension-free repairs significantly reduced recurrence rates and simplified operative strategies (Lichtenstein et al., 1989). Subsequent refinements consolidated the principles of tension-free anterior mesh repair and clarified technical details relevant to mesh placement and fixation (Amid, 2004).

However, widespread standardization of prosthetic techniques also led, in some settings, to a relative loss of individualized anatomical reasoning, with renewed emphasis on defect-oriented repair steps rather than comprehensive parietal reconstruction. Within this evolving landscape, the Parietal Inguinal Box Repair (PIBR) is proposed as a synthesis of classical anatomical principles and contemporary mesh-based concepts. PIBR is primarily intended for adult patients with primary inguinal hernias who are candidates for open repair, including those with contraindications to laparoscopy or in whom an open approach is preferred based on clinical judgment. Current guidelines continue to recognize both open and minimally invasive approaches as valid options in selected patients (Simons et al., 2009; Bittner & Schwarz, 2011).

In contemporary surgical practice, the persistence of open anterior approaches should not be interpreted as resistance to minimally invasive innovation, but rather as evidence of the continued relevance of direct anatomical control in selected clinical settings. Patient-related factors such as advanced age, comorbidities, previous pelvic surgery, or contraindications to general anesthesia may favor an open strategy, while surgeon-related factors, including specific expertise in anterior anatomy, further justify the maintenance of refined open techniques.

Within this framework, the distinction between defect-based and parietal-based repair becomes crucial. Defect-oriented strategies tend to focus on closure or coverage of the hernia orifice, whereas parietal reconstruction aims to restore the functional integrity of the inguinal region as a load-bearing unit. This conceptual shift, already implicit in Bassini’s original reasoning, acquires renewed significance in the mesh era, where prosthetic materials allow reinforcement of anatomical compartments rather than isolated defects.

PIBR is therefore not conceived as a competing alternative to posterior or laparoscopic repair, but as a complementary option within a spectrum of anatomically rational strategies. Its value lies in the deliberate integration of classical anatomical insight with modern prosthetic technology, preserving surgical intentionality in an era increasingly dominated by standardized procedural pathways.

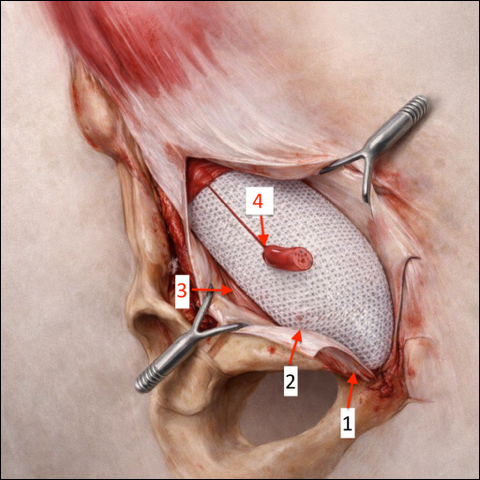

PIBR is performed through a standard anterior open approach under general or regional anesthesia. After incision and exposure of the inguinal canal, the external oblique aponeurosis is opened and the spermatic cord is identified. The cord and hernia sac are isolated as a single anatomical complex and gently suspended to allow clear visualization of the posterior wall.The hernia content is reduced into the abdominal cavity without dissection, ligation, or resection of the peritoneal sac. This step reflects the parietal rationale of the technique, in which the sac is regarded as a secondary manifestation of wall weakness rather than a primary surgical target.The boundaries of the inguinal box are then identified. A flat polypropylene mesh is tailored to accommodate the spermatic cord and positioned anteriorly to cover the entire inguinal compartment. The mesh is stabilized through selective three-point fixation to the pubic tubercle, the pubic ramus (pectineal ligament), and the inguinal ligament. Fixation is intentionally limited to these stable osteoligamentous landmarks to maintain a tension-free repair while ensuring mechanical stability.

The opening of the mesh around the spermatic cord is calibrated with a single suture. After verification of correct mesh positioning and absence of folding, the anterior wall of the inguinal canal is reconstructed and the wound is closed in standard fashion.

In selected cases, PIBR may also be applied to recurrent inguinal hernias following previous anterior repair, provided that local anatomy allows secure identification of fixation points.

The Parietal Inguinal Box Repair represents a coherent and anatomically grounded evolution of classical anterior hernia repair within the modern mesh era. It is not proposed as a novel operative concept, but as a structured refinement of anatomy-based principles adapted to contemporary prosthetic materials.

A defining feature of PIBR is its parietal, wall-centered rationale. By deliberately avoiding dissection or resection of the peritoneal sac, the technique redirects surgical attention toward the structural integrity of the inguinal wall. This conceptual shift is compatible with the functional interpretation of the myopectineal region described by Fruchaud and adopted by posterior and endoscopic repairs, while preserving the advantages of direct anterior visualization (Fruchaud, 1956; Wantz, 1991).

From a biomechanical and vector-based perspective, the selective three-point fixation strategy plays a central role in the stability of the repair. Increasing the number of anchoring constraints and optimizing the geometry of fixation allows mechanical loads generated by intra-abdominal pressure to be redistributed across multiple vectors. This triangulation concept is consistent with classical surgical-anatomy reasoning in abdominal wall reconstruction (Skandalakis et al., 1995; Wantz, 1991).

This configuration can be conceptualized as an inverse funnel, in which parietal forces are progressively transferred toward stable osteoligamentous landmarks. By reducing unit stress at each anchoring point, this geometry may decrease the risk of suture failure and recurrence while limiting prosthetic material and fixation to what is strictly necessary.

Compared with other anterior mesh techniques, PIBR emphasizes selective rather than diffuse fixation. Techniques such as the Lichtenstein repair and subsequent refinements have emphasized standardized anterior mesh placement and fixation patterns. Lichtenstein et al. (1989); Amid (2004) By limiting fixation to three stable anatomical points and avoiding unnecessary sutures, PIBR aims to minimize tissue trauma and potential nerve irritation, which may be relevant in reducing the risk of chronic postoperative pain.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. PIBR is an open technique and therefore shares the inherent constraints of anterior surgery. In addition, the present work focuses on anatomical rationale and technical description rather than on comparative clinical outcomes. Prospective studies will be required to evaluate long-term results, postoperative pain, and recurrence rates in comparison with established techniques and guideline-based recommendations (Simons et al., 2009; Bittner & Schwarz, 2011).

A further consideration relates to the dynamic behavior of the inguinal region under physiological conditions. The abdominal wall is subjected to repetitive cyclic loading generated by respiration, posture changes, and increases in intra-abdominal pressure. In this context, repair stability depends not only on the strength of individual anchoring points, but also on the overall geometry of fixation.

From a vector-based perspective, fixation limited to two points may concentrate tensile forces along a single axis, increasing stress at the suture–tissue interface. The addition of a third anchoring point modifies force distribution by introducing triangulation, which allows forces to be decomposed into multiple vectors and dispersed across a broader area of the parietal framework. This principle is well recognized in structural mechanics and finds a direct anatomical correlate in the osteoligamentous boundaries of the inguinal region.

The resulting configuration may be viewed as a mechanically efficient support system, in which stability is achieved not through increased material or excessive fixation, but through optimization of anchoring geometry. By reducing peak stress at each fixation site, this approach contributes to long-term durability of the repair while respecting surrounding tissues and minimizing the biological cost of fixation.

The conceptual foundations of PIBR can be traced to the Italian anatomy-based surgical tradition originating in the Padua school. This lineage, initiated by Bassini and preserved through successive generations, emphasized meticulous anatomical dissection and disciplined operative technique. Bassini (1887); Bassini (1890) Guido Oselladore represents a central figure in the transmission of these principles to Milan, where they influenced the development of modern Italian surgery. Historical reconstructions of this Padua–Milan lineage have been documented in the Italian surgical literature (Montorsi, 1985).

The Parietal Inguinal Box Repair integrates classical anatomical principles with contemporary mesh-based surgery through a parietal, wall-centered approach. Selective three-point fixation provides a mechanically rational and reproducible method within modern open inguinal hernia repair.

None Declared.

None.

Not applicable

- Skandalakis, J. E., Skandalakis, P. N., & Colborn, G. L. (1995). Surgical Anatomy of the Inguinal Area. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Bassini, E. (1887). Nuovo metodo per la cura radicale dell’ernia inguinale. Arch Ortop, 4, 380-388.

- Bassini, E. (1890). Sulla cura radicale dell’ernia inguinale. Riforma Medica, 6, 1-10.

- Fruchaud, H. (1956). Anatomie chirurgicale des hernies de l’aine. Paris: Masson.

- Nyhus, L. M. (1995). The Preperitoneal Approach and Iliopubictract Repair of Inguinal Hernias. In: Nyhus, L.M. and Condon, R.E., (Eds.), Hernia, (4th ed., pp. 153-177). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1379744

- Wantz, G. E. (1991). Abdominal Wall Hernias. New York: Springer.

- Lichtenstein, I. L., Shulman, A. G., Amid, P. K., & Montllor, M. M. (1989). The tension-free hernioplasty. Am J Surg, 157(2), 188-193. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9610(89)90526-6

- Amid, P. K. (2004). Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: its inception, evolution, and principles. Hernia, 8(1), 1-7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-003-0160-y

- Simons, M. P., Aufenacker, T., Bay-Nielsen, M., Bouillot, J. L., Campanelli, G., Conze, J., de Lange, D., Fortelny, R., Heikkinen, T., Kingsnorth, A., Kukleta, J., Morales-Conde, S., Nordin, P., Schumpelick, V., Smedberg, S., Smietanski, M., Weber, G., & Miserez, M. (2009). European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia, 13(4), 343-403. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7

- Bittner, R., & Schwarz, J. (2011). Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal hernia. Hernia, 15(1), 1-20.

- Montorsi, W. (1985). Guido Oselladore e la scuola chirurgica milanese. Minerva Chir, 40, 1245-1250.

Anatomical landmarks for open inguinal hernia repair (right side):

- Pubic tubercle – medial fixation point for the mesh.

- Pubic ramus / inguinal ligament – site of mesh anchoring along the inferior border.

- Distal insertion of the inguinal ligament – lateral fixation point to secure mesh coverage of the inguinal canal.

- Keyhole around the spermatic cord – the mesh is gently closed around the cord without compression, to maintain physiological passage.