Article / Research Article

1University teacher, Autonomous University of Nayarit

2Master degree, University teacher, Autonomous University of Nayarit

3Psychology, University Teacher, Autonomous University of Nayarit

Dr. Alejandro Ochoa Pimienta

University Teacher,

Autonomous University of Nayarit

31 January 2023 ; 21 February 2023

The university environment entails carrying out a great diversity of productive activities. All of them are carried out without detriment to the academic obligation, which implicitly involves occupational pressure on the students who decide to venture into any of the activities foreseen in the student work since all of them require the availability of time, dedication, tenacity, perseverance, and both physical and mental resistance due to the effort that is necessary to carry them out for their execution.

Sport is part of the great diversity of activities that university students can carry out. Its practice involves observing the various situations that can affect sports performance, even though it does not correctly refer to obtaining prizes or medals, since if only these arguments are considered to evaluate the implicit process in sports practice, subjective observation of dominance in case of being winners, even of failure if it occurs, since to a large extent the difference between winning or losing is not only due to having greater/less athletic physical capacity, since to enormous size the athletes who compete both individually and as a group and who are capable of making use of their full potential, are those who have managed to adapt to the prevailing conditions during their processes, that is, they have managed to control as much as possible their variables involved in sports performance.

Team cohesion is one of those variables, which for its consolidation requires harmonizing a large number of internal and external factors, the barometric conditions in which training sessions and competitions occur, and practice schedules that can be combined with school schedules. That hinders the joint and effective performance of both activities since it is essential to mention that athletes are obliged to maintain their level of efficiency in both contexts, hence the performance of both tasks could at any given time be a factor that generates anxiety with Sufficient potential to alter the state of mind that promotes a modification of the emotional state powerful enough to change the perception of the athlete, causing cognitive distortions complex enough for the athlete to make accurate assessments of the origin of such tensions.

Hence the importance of knowing the factors that alter the team cohesion of the athletes studied is manifested in the psychological disposition with which they face sports and social demands and the coping skills they have developed throughout their experience.

Lev Pavlovich Matveev published 2001 his book entitled: General theory of sports training; in this work, he establishes in an organized way the historical origin of what is currently known as a sport; in the same way, he presents the differentiation that exists between physical activity and sports practice. First, the activities that are carried out are focused on carrying out motor actions and on the education of essential physical capacities, such as the case of the development of strength, resistance, and speed in a very general way. In sports activity, more specialized actions are carried out with precise rhythms and sequences whose primary purpose is to obtain baskets, points, goals, etc.

In both activities, philosophical-methodological and cultural aspects must invariably be considered to achieve efficient execution and observation in its development. On the one hand, we have then that the biological elements include anthropology, morphology, biomechanics, and physiology; on the other hand, in the humanistic aspects, sports history, sociology, aesthetics, ethics, psychology, and psychopedagogy are grouped.

So then, the biological aspects involve, among other things, anthropological tendencies. Within this, it will be possible to see a greater ethnographic tendency to carry out some physical or sports activity. Similarly, the morphology of a subject establishes the biotype for a particular activity where athletes can be more efficient. In this sense, biomechanics entails specific movements with maximum efficiency and minimum physical effort. And finally, physiology refers to the ability that athletes develop to assimilate physical loads and increase their level of overcompensation, that is, gradually increasing their level of sports performance.

Regarding the humanistic aspects, the historical and family background that affects the choice of a specific sport practice is considered. The social factors that a particular sporting activity entails are basically due to the media trend and, above all, to the presence of large and attractive sporting events that many people usually see. The aesthetic and the ethical are related to the execution of the different sports routines within a framework of operating rules. The psycho-pedagogical aspect is associated with how the novice practitioner is shown and introduced to more demanding spheres of execution. And finally, the psychological element involves taking into account the psychological variables involved in physical and sports performance.

Therefore, it can be observed that carrying out a physical activity or practicing a sport necessarily involves taking into account aspects that must be carefully monitored to measure them and determine at a given moment which element of the sporting activity is to be considered. Must attend to contribute to perfecting the athlete.

Thus, this article focuses on the humanistic aspects of a psychological type, notably the psychological variables involved in sports performance, and specifically the team cohesion presented by the athletes participating in this research.

The motor activity involves developing, in equal measure, cognitive and physiological functions that favor the human being with a greater capacity for understanding and, in turn, a better adaptation to the environment in which it develops. Regular sports practice contributes significantly to improving this adaptive capacity. This is why sport plays a vital role in man’s and society’s evolution.

“The main social function of sport in modern society is precisely its adaptive, biological, and psycho-regulatory role that provides the individual with the necessary motor activity to achieve transcendence in all spheres where man lives” (Zhelyazkov, 2001).

However, sports activity is usually carried out due to various interests, and of these, the ludic benefit is generally widespread; this is because its very execution allows a certain degree of freedom of movement and actions; however, as progress is made in its practice, the complexity increases and the execution standards are more and more demanding, as time goes by and as a product of the same course, a more significant improvement is achieved, paradoxically this leads to the athlete being more rigorous with himself due precisely to the same efficiency developed.

Hence, this same intrinsic desire for positive evolution can cause him not to realize that many factors are involved in the practice itself, some of which are not inherent to the athlete himself, some of which are external, such as the context., teammates, the coach, the temperature, the different personalities, etc., that is, there are personal, environmental, and contextual variables that, affect sports performance in one way or another.

This indicates that when athletes have a particular obsessive or harmonious passion, there is greater team cohesion; being able to observe that in competitive athletes, the perception of obsessive desire prevails, and in recreational athletes, harmonious passion, but all this about team cohesion leads to success. However, even more, cohesion can be observed in competitive athletes, perhaps because they are aware that cohesion is a fundamental aspect for the proper functioning of their team since,

for these athletes, The main goal is the sporting performance itself, which is evident through the trophies and medals obtained, that is, positive results, since they take into account the relationship with their teammates, in addition to the fact that each one of the team members seeks common goals, while the purpose of recreational athletes may vary. Paradis, Martin and Carron. (2012).

Hodgetts R. (1989) describes how “personality traits influence how the individual interacts and behaves with other team members” (p. 74), which indicates that the behaviors in groups are partly the result of the personality characteristics of each individual.

On the other hand, García A. (2010) argues that there are some methodological problems when assessing the personality of athletes, as he argues that discrepancies are observed among some researchers. Rhodes and Smith (2006) conducted a literature review on the main personality traits in sports. They concluded that some variables could be related to personality and sport, such as gender, age, culture/country, design, and the measurement instrument. However, there are no conclusive results invariant to the results obtained, recommending a more significant number of works that integrate these variables to clarify these aspects.

However, authors such as Cox (2002), Vealey (2002), and Weinberg and Gould (2007) show that the lack of definitive conclusions in personality research in the sports context is mainly due to methodological problems, recommending more from different models and methodologies. The criticisms of these authors are primarily focused on the variety of theories and instruments used in personality analysis, the distance between evaluation and psychological theory, the difficulty of constituting the study sample, the use of small pieces, and the limitation to replicating research and intercultural studies.

There is a great variety of theories and instruments in the study of personality (Alderman 1983; Núñez 1998; O’Sullivan, Zuckerman, and Kraff 1998). The different tools designed may not evaluate the same personality factors, and the results obtained are interpreted from other theories. In the same way, a distance between evaluation and psychological theory prevails. Since, in general, in the study of personality, there is often little, or no attempt to formulate hypotheses or explain conclusions, similarities or variations in the data are described without a theoretical context from which to interpret the results (Pelechano, 1996).

The insistence on evaluation questions measured with instruments has brought the loss of psychological theory because the insistence on measurement and the technique or instrumental evaluation procedures makes it difficult to create basic content sciences.

Many studies in the sports context have compared personality traits between athletes of different sports, levels of competition, or between athletes and non- athletes without a frame of reference (O’Sullivan, Zuckerman, & Kraff, 1998). This measurement trend has made it possible to save resources and has allowed an objective and quantitative estimate of comparison between the personalities of different athletes. Character is what personality tests measure, with which the psychology of personality tests has progressively separated from the psychology of athletes’ personality research; In contrast, the first has studied products, and the second insists much more on processes. Therefore, both the personality assessment and the theoretical model on which the instrument is based and the explanation of these results are essential.

Another aspect to consider is the difficulty in constructing the study sample. Well, there may be various subgroups among athletes depending on the level of practice (Bara, Scipio, and Guillen, 2005; Guillen and Castro, 1994; Valiant, Simpson- Housley, and McKelvie, 1981), sex (men vs. women) ( O ‘Sullivan, Zuckerman, and Kraff, 1998; Schroth, 1995), age or category (child, cadet, junior, adult) (Ruiz 2005) and the sport modality that is practiced (individual vs. group or type of sport) Cox, 2002; Bara, Scipiao and Guillen 2004).

Regarding undersized samples (Vealey, 1992), there is great difficulty accessing high-level athletes who wish to participate in research, so small subjects are usually used. Hence the results are not always representative of the reference population. In this sense, many of the results obtained in the different investigations are not replicated in subsequent studies, so they cannot be considered conclusive. And finally, it is essential to think that most of the studies have been carried out with samples of athletes, preferably North Americans, and very few with athletes from other parts of the world. Hence, the results of the investigations are not always generalizable to other populations or cultures.

From the review of previous research papers, it is possible to establish that athletes tend to show a higher level of optimism, are more oriented towards pleasure, and offer a higher level of activity when it comes to achievement motivation. In what corresponds to the cognitive modes, their source of self-evaluation is preferably external. Regarding interpersonal relationships, they are friendlier, dominant, and aggressive than non-athletes. In the same way, it was possible to observe the relationship between the Psycho-sports variables and sports performance.

Therefore, the central premise that the athletes representing the University should be privileged is the academic demand. After this statutory instance, the lifestyle and family life of the athlete himself come as a consequence. These aspects can influence the athlete’s performance at a given moment, so it may be necessary to attend to these demands in a particular way.

From the systemic point of view proposed by Bertalanffy (1969), this perspective suggests that if there is an alteration in any of the dimensions mentioned above, or if too much attention is paid to it, other sizes can be neglected as a consequence, and this, Sooner or later it can cause situations that do not contribute to competitive efficiency.

However, if we observe this dynamic, the execution of these dimensions will not always be loaded with stress or tension; on the contrary, all the activities can contribute in turn so that the athlete, during his execution, alternately develops a ludic and social action, Consequently, this will be reflected in a state of mind oriented towards effort and dedication (Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi, 2010), but equally, also if achievement expectations are established that do not correspond to the reality of action and execution of the athlete as well. It can cause you disappointment and frustration and therefore lead to an alteration in your various spheres of personal development.

Therefore, this variation could be reflected in a psychological disposition that does not contribute to the maintenance and achievement of previously established goals (efficiency and optimal performance); this possible variation and limitation of interpretation may lead to dissatisfaction and despair in the athlete and possibly reflect this sensation in behaviors of detachment and avoidance in other activities.

Because of those above, it is necessary to support the athlete to develop his resources not only in the sports field but also to transcend his potential to other spheres of his life. Since the human being is endowed with sufficient capacities to reach an optimal level of functioning that provides the ability to face daily demands and to function adequately in the different areas that correspond to human development.

The performance of sports activity encompasses a large number of factors of an individual, social, family, academic, affective, spiritual type, etc. All of them, in one way or another, affect the athlete’s mood and are manifested during their active process in the form of variables, which can be altered due to environmental events in which the athlete lives. As stated in the introduction, the main functions closely addressed in sports psychology are precisely oriented toward the analysis and study of the variables that influence the performance of athletes, obviously considering all the areas and phases where it is carried out the same. Since as previously stated, it is not the same to carry out a specific sports routine in training as to carry it out in a competition, that is, in training, the athlete becomes familiar with the environment and his teammates, and therefore it may be more agile to adapt and thus regulate their variables, on the contrary, in a competition the external agents multiply, which results in internal agents being affected, that is, the athlete’s variables, which could in a given moment be reflected in sports performance.

The objective of this research work was to determine, according to the model of Carrón, Brawley, and Widmeyer (1998), what type of team cohesion prevails in the Autonomous University of Nayarit athletes, and how does it affect interpersonal relationships?

This model postulates the presence of two implicit dimensions in group cohesion.

In the first, he supports the existence of task-oriented cohesion, where group members work together to achieve common goals, and in the second, called social cohesion, where team members experience empathy with each other. As a result, they enjoy the fellowship of the group. Another theoretical model proposed by Zander holds;

“The process of interaction in the group through a certain time generates different results that become evident when the group members become familiar with each other and develop feelings of empathy and antipathy, thus establishing a more attractive structure. Or less stable” Zander, (1979)

By group composition, some members behave more dominantly than others and contribute more to goal attention and task performance. If a structure has not been established at the time of group composition of influence, leadership, or a social power structure, power struggles will be generated.

Sport is only a part of human activity; it is in this activity where theory and practice, science and art are intertwined, in such a way that carrying out a unilateral analysis of this activity may be inappropriate since the ability sports is a complex phenomenon, since, although the final result is analyzed as the leading indicator of efficiency, it is also necessary to consider other aspects that are closely linked to this process (Gorbunov, 1988), therefore, within the analysis of the Sports activity will have to take into account the factors that promote athletic practice in people, the personal, social, family, and sports background of the athletes themselves, the incidence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Buceta, 1998; Vega, 2002).

It is worth emphasizing the importance of interpersonal relationships with the same teammates, the relationship with the coaches, and even at a given moment, also consider the anthropomorphic characteristics of the practitioner since each sport and position have different parts of the performance. Which in turn favors the creation of micro-alliances between partners? These body characteristics are taken into account by the coaches of the other sports disciplines since they designate the positions that the athletes will have to execute during their sporting process. At a given moment, they can represent some competitive advantage.

Regardless of any reason why the youngster is immersed in the sports field, every one of the participants must first direct their activity towards the development of physical abilities, that is, strength, resistance, and speed (Zhelyazkov, 2001), every time they manage to fine-tune these physical qualities, they must develop technical attributes, that is, specific rates depending on the type of sport and whose leading utility is concentrated in an economy of movements, which implies carrying out the best execution with the minimum of physical effort and with the most outstanding possible efficiency (Buceta, 1998).

In another order of ideas, it should be noted that once the high-performance athlete manages to increase his technical efficiency, he must learn strategies that provide direction, consistency, efficiency, and desired results; for this, it will be necessary for the participants to carry out a systematic way, individual and joint routines of a tactical type that contribute to the expected achievement.

It is interesting to emphasize that such activity specification must be carried out in two closely linked scenarios but with different orientations; on the one hand, it is necessary to carry out all this action in training whose primary purpose is to fine-tune technical/tactical skills, and to carry out a and again, the different routines to achieve the maximum possible level of control over the execution. On the other hand, once you are adequately prepared, these skills will be tested in a state, national and international competition.

So then, training and competition become the two main scenarios where the athlete will see his physical effort reflected; however, this constant effort will invariably imply physical preparation. Therefore, the psychological practice should also be considered part of the sports process.

In this sense, from a purely practical point of view, it is possible to infer that there will be some athletes who direct their attention to efficiency, that is, to the result, and for this, they concentrate all their energy on achieving a satisfactory result, such is the case of winning a medal, obtaining a mark, etc., without taking into account implicit

factors in the sporting practice itself, such as the interpersonal relationship with one’s teammates and even the interrelationship with coaches, or external aspects that can undoubtedly influence the final result, and then by not getting what they wanted, they end up being victims of their disapproval and even transfer it to other areas that do not correspond to sports (Mahoney, 1974), for example, school, family, friends, etc.

Some athletes will probably enjoy the activity just because they want to be physically fit or they want to be close to someone they might be interested in; others, perhaps, will seek family approval within the sporting activity, since in the family itself, it becomes a tradition to be a sportsman.

In short, interests and intentions may vary, but what does not vary at all is that carrying out the sporting activity requires a lot of time and, above all, a lot of physical and mental effort; In particular, an ongoing interpersonal relationship with the coach and with teammates is required, for this reason, it implies persistent mental exhaustion in the athlete, this situation can lead to alterations in team cohesion that favor or failing that, limit sports performance.

When referring to team cohesion, it necessarily involves considering various sciences and factors that are related to the term itself, such as psychology, sociology, training, and competition, as well as the correlation of these in the behavior of the human being; this is considered as a social being by nature, hence the need to interact with other individuals.

According to Hodgetts and Altman (1989): “A group is a social unit consisting of several individuals who play a role and have status relationships with each other” (p.150); that is, each person has a specific function, and different from the others for the search of a common goal thus forming part of an organization.

There is a similarity in terms of the characteristics that sports groups have in their objective and operation with the therapeutic meeting groups presented by Dr. Celedonio Castanedo in his book Meeting groups in Gestalt therapy (1990, 1997, 2003). In the theoretical foundations of the meeting groups, it is established that they are a way of establishing a good human relationship, which is obtained from open communication between the participants, later this author adds that it is essential for its proper functioning that there is among the members’ honesty, awareness, responsibility and above all paying attention to the emotions that emanate from the members of the group, and something very relevant that he considers in this foundation, refers to the fact that the meeting groups emphasize at all times the concept existential of the here and now, together with the how, that is, the members of the therapeutic encounter groups focus their attention on the present moment and on finding the reasons why the situation in which the subject finds himself.

In this sense, a good part of the members of sports groups tends to focus on developing motor skills, either technically or tactically. For this reason, they leave and neglect the incorporation of social skills. Therefore, they do not assume full awareness and responsibility that their group participation involves using these two abilities. And another element that is added to this dynamic of group evolution refers to the fact that many of the activities that are carried out in the sports field are carried out precisely to anticipate some competitive contingency that may arise in the competition; perhaps for this reason, they forget to live in the here and now, that is, they do not assume full awareness of living in the present, or even many team members or the coach himself, try to relive and remedy past situations in daily training.

The instrument called FIRO-B (Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation – Behavior), as its name indicates, allows us to measure the fundamental profile of interpersonal relational orientation based on the behaviors that emit inclusion, control, and affection that athletes want and express.

A particularity that the FIRO-B model presents is that all its scales are Guttman. This establishes that predictability is the product or result of the appropriate measure of internal consistency, so then, if the items have the cumulative property, their one- dimensional measure is accepted. Predictability is a more rigorous criterion than the usual method of measuring internal consistency since it does not require that the items measure the same dimension. The Guttman scale is a procedure or technique to determine specific properties of a scale, of a set of objects, based on the fact that some things indicate to a greater extent the intensity of the attitude; the scale aims to analyze whether the items are reproducible or scalable. Reproducibility is presented based on the total score of each person since it is possible to reproduce their score in each item, and there is scalability if the things have different intensities since they represent different degrees of attitude. Both characteristics are related and assume that things are one-dimensional. (that measure a single dimension), so then the FIRO-B model allows evaluating the profile of prototypes that prevails in the athletes of the Autonomous University of Nayarit reliably, concerning the desired and expressed inclusion, regardless of the types of predominant personality in the sports as mentioned earlier universe, which could reveal the presence of multiple characters, however, the investigative spirit of this article does not intend to determine such a dimension, but rather, aims to observe the desired or expressed level of inclusion predominant for that, depending on the prevalence, determine its influence on team cohesion.

The concepts included in the three-dimensional theory refer to the interpersonal dimensions, of which there are three basic ones: Inclusion, Control, and Affection.

Inclusion relates to people who tend to show a great need to feel included in group activities, which is why they tend to express their desire. Other people with an introverted tendency opt for withdrawal and avoid confrontation or the match. They avoid associating with others and do not accept invitations to join others. They keep their distance from other people and do not mix with them. They unconsciously want attention for what can be said according to this three-dimensional theory that they want to be included. Three inclusion prototypes are established within this same inclusion dimension: little social, excessively social, and social.

For practical purposes and due to the central theme of this article, we will focus only on the inclusion dimension, both expressed and desired.

The FIRO-B measurement formula allows an approach to the concept of compatibility, which is based on the scores obtained after its application. The FIRO- B has been drawn up to measure not only the individual characteristics of people but also evaluate the interrelationships between people, such as compatibility. Mismatches are of two types: exchange mismatches, which are differences in the total amount of interpersonal exchange desired, and initiator mismatches, which are differences related to who initiates and receives the behavior.

This analysis will be approached from the perspective of the three-dimensional theory according to Schütz (1960), which refers to interpersonal dimensions, and establishes that there are three fundamental dimensions: the first, which is inclusion, which primarily describes that people tend to show a great need to feel included in the group’s activities, which is why they tend to express their desire, while other people with an introverted tendency who opt for withdrawal and avoid confrontation or confrontation. They avoid associating with other people and do not accept invitations to join others; that is, they keep their distance from other people and do not mix with people. They instinctively want attention, so according to this three- dimensional theory, they want to be included. Three inclusion prototypes are established within this same inclusion dimension: little social, excessively social, and social.

The scales presented by the FIRO-B approach are intended to help people realize themselves and, in turn, become aware of their way of relating to people. It is essential to point out that in this test, there are no correct or incorrect answers; the scores obtained allow people to know how they perceive or describe themselves.

Specifically, based on the results obtained, people can become aware of their reality, which does not mean they cannot modify it. It is based on the premise that when people realize how they relate, they will be able to face their interpersonal relationships more effectively in the future.

It is a commonplace that early experiences lead to anxiety or, failing that, that it manifests itself in extreme behaviors regarding inclusion; for the same reason, these extremes manifest themselves in excesses or deficiencies; hence, after knowing the results of the inclusion scale, if the subjects work hard and efficiently in interpersonal relationships, they will reduce the signs of anxiety.

The dimension of the inclusion prototype is manifested in three types of behaviors which are mentioned below:

A prototype of slight social inclusion manifests itself when the subject presents a low-expressed and desired inclusion.

An unsocial person tends to be introverted and prefers withdrawal to confrontation or confrontation. Avoid associating with other people and do not accept invitations to join others. He keeps his distance from others, does not mingle with people, or loses his privacy. This person unconsciously wants others to pay attention to him. Her great fear is that people will ignore her, not be interested in her and leave her aside.

Since no one cares about her, she won’t risk being ignored; she will stay away from people and do things independently. To exist from others, she will use self- sufficiency as a technique. Because social abandonment is equivalent to death, she will compensate by directing her energy toward survival and creating a world of her own in which her existence is more secure. In her withdrawal, she will feel anxious and hostile, feelings that she will hide behind a façade of superiority, and her conviction that others do not understand her and are not needed.

Her primary anxiety will be feeling devalued. Since no one considers her essential enough to pay attention to her, she will think she is worthless. This emotion hides a lack of motivation to live. It is often asked why we live.

A little social person does not associate with people and loses the desire to live. To a large extent, the degree of commitment determines the general level of enthusiasm, perseverance, and involvement. To someone like that, life offers few gratifications. Consequently, pre-life, that is, death, is desired. The most substantial fear is the fear of abandonment or isolation.

The prototype of excessive social inclusion manifests itself when the subject presents a highly desired inclusion.

An excessively social person constantly looks for people and wants others to see them and always be with them. He is afraid of being ignored, and his primary emotion is the same as that of the unsocial person, even though his overt behavior is the opposite.

Although she constantly doesn’t allow herself to realize it, she experiences a feeling that nobody cares about her; responding to that emotion gets people to pay attention to you at any cost. She always inclines to seek company; she cannot bear to be alone. She designs all her activities to run with someone. For such a person, being close to someone is an end in itself. She tries to attract attention so that people notice her and be heard. One technique she uses to achieve this is by being an active, deep participant and exhibitionist. To attract attention, you can try to gain power (control) over others or be appreciated (affection) by others. However, although both (strength and friendship) are essential, they are not his fundamental goals.

The social inclusion prototype manifests itself when the subject presents a moderate inclusion expressed and desired.

For a social person, who as a child did not present any problem in resolving inclusion situations, interrelation with people will not cause conflicts either; he will feel good with or without people in a group, and he can participate a lot, somewhat or not at all, without the degree of their participation giving rise to any anxiety. If he sees fit, he can get very involved with specific groups. You can also suspend or cancel a commitment made. She feels valued, considers herself a significant person, and is committed to her whole life. She never has the feeling of being nobody, of being useless. She has not had in her childhood feelings of confusion in her identity that come from the negative confluence. On the other hand, she has integrated the positive aspects of many people who have been significant in her childhood (introjection).

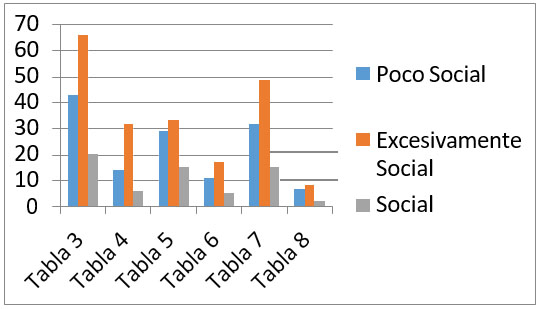

| Table 3 | Table 4 | Table 5 | Table 6 | Table 7 | Table 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little social | 43 | 14 | 29 | 11 | 32 | 7 |

| Excessively social | 66 | 32 | 33 | 17 | 49 | 8 |

| Social | 20 | 6 | 15 | 5 | 15 | 2 |

Source: self-made

Table 15: The generalized trend of the prototype Inclusion of the total

Source: self-made

Source: self-made

Figure 1: Prototype trend Inclusion of all tables

As seen in Table 15 and Figure 1, in all the tables, there is a predominance of the excessively social type of inclusion prototype, which consists of these people constantly looking for people and wanting to be seen by others. And always be with them. They fear being ignored in such a way that their primary emotion is anxiety, which they reduce with extroversion behaviors. Since her inclination is always to seek company, she cannot bear to be alone. Design all your activities to run with someone. For such a person, being close to someone is an end in itself. It tries to attract attention so that people notice it and be heard.

In contrast, the second trend in participation of the population of athletes is little social, which is manifested by being introverted and opting for withdrawal to confrontation or confrontation. And something relevant that they reveal is that they tend to avoid associating with other people and do not accept invitations to join others. They keep their distance from others so they don’t mix with people. However, he will use self-sufficiency as a technique to exist from others. Because social abandonment is equivalent to death, he will compensate by directing his energy toward survival and creating a world of his own in which his existence is more secure. In her withdrawal, she will feel anxious and hostile, feelings that she will hide behind a façade of superiority, and her conviction that others do not understand her and are not necessary.

Therefore, it can be established that there are two significant interests since, on the one hand, a little more than half of the population of athletes tend to show a desired high inclusion that is manifested in excessive social behaviors. On the other hand, a third of the population prefers to display introverted behaviors, which is why they keep their distance from other people. Therefore, it is possible to infer that the athletes have a common purpose: to seek and work together toward a goal. The way to carry it out based on their respective personalities can promote anxiety outbreaks among athletes, coupled with the fact that competitive demand is per se a stressor factor with sufficient potential to become the leading cause of not being able to amalgamate adequate group cohesion.

In summary, based on the results of the cross-sectional application of the FIRO-B in the population of athletes from the Autonomous University of Nayarit, it is possible to conclude that the prevalence of the excessive social inclusion prototype is constant in the different tables with its consequent particularities is the main factor by which athletes do not achieve adequate team cohesion because as mentioned above.

For athletes to achieve their goals, they must establish relationships with people who share their same orientations and desires and thus initiate a link that, according to Berscheid and Ammazzalorso (2004), refers to two people whose behavior is interdependent in terms of the change of behavior in one probably produces a difference in the conduct of the other, this interdependent behavior causes a closeness which refers to a pattern of interaction in which the behavior of each one of the parties depends a lot on the behavior of others. The other. This is why a close relationship is often seen as one in which the parties are highly interdependent. The relationship takes place over a long period; each party’s influence on the other is strong and frequent, and consequently, many different types of behavior are affected.

Hence, this process of interrelation between two or more subjects for prolonged periods gives rise to what is known as proximity itself, which is a way for strangers to get to know each other because the proximity between the residence of two people establishes that at a minor physical distance, the greater the likelihood that those two people will come into repeated contact, and thus experience repeat exposure.

Repeated exposure refers to frequent contact with a stimulus; according to Zajond’s(1968) theory, repeated exposure to any moderately negative, neutral, or positive stimulus results in an increasingly positive evaluation of that stimulus. This explanation refers to the fact that we usually respond with at least moderate discomfort when we meet someone or something unknown. A familiar face is not only evaluated positively, but it generates positive affect and stimulates facial muscles and brain activity in a way that indicates a positive emotional response. The familiar face is directly related to the word family, and repeated exposure allows new people and aspects of the world to be included in the extended family. However, even though the effect of repeated exposure has been demonstrated in many experiments using many different stimuli, Hansen and Bartsch (2001) suggested the possibility that not all people respond equally to the effect of exposure.

An aspect that can negatively influence this continuous exposure and that can trigger negative affective responses in the athlete from the Autonomous University of Nayarit is precisely due to the double function that athletes are obliged to cover, that is, athletes must attend academic demands as well as sports demands, so they must remain for long periods on the university campus, and for this reason, it can become an agent with sufficient potential to generate stress, which in the end can detonate in moods not conducive to coexistence. Therefore, if one adds the fact that excessively social prototypes prevail, they can become the main antecedents that, according to Carrón (1982), affect the development of cohesion in the field of sport and physical exercise; in this sense, it refers to the factors environmental, personal factors, leadership factors and those of the structure of the team’s functioning, in this particular case we are referring to the ecological aspect where the athlete lives and the psychological element that manifests itself in the psychological disposition of the athlete. And within the personal factors, we can consider precisely the data that was shown in the participant’s section, where it can be observed that there is a great diversity of places of origin of the athletes, in addition to the fact that students from other careers also attend who demand their study of specific academic requirements that are sometimes difficult to match with sports practice. In this same sense, the semester that athletes take can, at any given time, mean a greater demand for attention that will ultimately be reflected in sports performance.

- L.M., Woehr, D.J., &Poling, T.L. (2008). The impact of diversity of values in teams on process variables and task performance. Latin American Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 523-538.

- Bakker, Whiting, H. & Brug, H. (1993). Sports psychology. Concepts and applications. Madrid: Morata.

- Barbary, (2002). Physiology of exercise and training. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Baron, A. Byrne, D. (2005). Social psychology. Madrid: Pearson Prentice Hall

- Bleger, (1999). Behavioral psychology. Mexico, DF: Paidotrivo.

- Buceta, (1998). Psychology of sports training. Madrid: Dickinson.

- Buceta, (1995). Psychological intervention in team sports. Journal of General and Applied Psychology, 1, 95 – 110.

- Gross, R. (2007). Psychology. The science of mind and behavior. Mexico, DF: Modern Manual

- Caballo, E.V. (2008). Manual of therapy techniques and behavior modification. Madrid: Twenty-first Century of

- Castanedo, C., and Murguía, Gabriela (2001) Diagnosis, intervention and research in humanistic psychology Madrid:

- Castanedo, (2003). Meeting groups in Gestalt therapy. Barcelona: Herder.

- Chicau Borrego, , Silva, C., & Guerrero Palmi, J. (2012). Psychological Intervention Program for Optimizing the Team Concept in Young Soccer Players. Journal of Sports Psychology, 21 (1), 49-58.

- Cox, R. (1985). Sport Psychology concepts and their application. Madrid: Pan

- Cox, (2009). Sports psychology. Buenos Aires: Pan American.

- Cueli, J. Reidl, L. Martí, C. Lartique, T. Michaca, P. (1990) Theories of personality Mexico: Trillas

- Dietrich, M. (2004). A general methodology of child and youth training. Barcelona:

- Dietrich, Klaus, C. Klaus, L. (2007). Sports training methodology manual. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Denis, R. (2001). 80 questions and answers about the athlete’s diet: the most frequent questions in physical exercise and sports Madrid: Hispano Europea.

- Erez, , & Isen, A. M. (2002). The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 1055-1067.

- Garcia F, Puig B, N. Lagardea O, F. (1998). Sports sociology. Madrid: Alliance.

- Garcia-Mas, A. Vicens, P. (1995). The psychology of the sports team. Cooperation and Sport Psychology Journal. 6, 79-89.

- Garcia, , Puig, N. and Lagardea, F. (1998). Sports sociology. Madrid: Alliance

- Garcia, A. (2010). Individual differences in personality styles and performance in Report to qualify for the degree of doctor. Faculty of Psychology, Complutense University of Madrid.

- Gibson, J. Ivancevich, J. Donnelly, J. (1994) Organizations. Wilmington:: Addison- Wesley

- Gonzalez, J., Sánchez, P., and Mataix, J. (2006). Nutrition in sport. Ergogenic aids and Madrid: Diaz de Santos.

- Hodgetts, Altman, S. (1989). Behavior in Organizations. Mexico: McGraw-Hill.

- Guerrero, J. (1994). Cohesion and performance in team sports: Experience in high- performance roller Physical education and sport. 3, 38-43.

- Hodgetts, Altman, S. (1989). Behavior in Organizations. Mexico: McGraw-Hill

- Iturbide, L., Elousa, P., and Yanes, F. (2010). Cohesion measure in sports teams— Spanish adaptation of the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ). Psychothema, 22 (3), 482-488.

- Jackson, Csikszentmihayi, M. (2010). Flow in sport Badalona: Paidotribo

- Heinemann K. (2003) Introduction to empirical research methodology in sports Barcelona Paidotribo

- Klineberg, O. (1965). Social Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. Mexico: Economic Culture Fund

- Kossen, (1995). Human resources in organizations. Mexico: Harla.

- Leo F., García T, Parejo I, Sánchez P, and Sánchez D, (2009). Interaction of cohesion in perceived efficacy, expectations of success and performance in basketball teams, Revista de Psicología del Deporte, (19)89-102.

- Marcos, F., Calvo, T., González, I., Miguel, P., and Oliva, D. (2010). Interaction of cohesion on perceived efficacy, expectations of success, and performance in basketball teams. Journal of Sports Psychology, 19 (1), 89-10.

- Matveev, L. (2001). General theory sports training. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Medina J, (2003). Physical activity and integral health. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Menendez, E. (2002). From individual work to teamwork: Esdai Hospitality, (2), 83-

- Omenaca, Puyuelo, E. Ruiz, J. (2001). Cooperate: theoretical bases and units for school physical education approached from the activities, games, and methods of cooperation. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Orlick, (1990), In pursuit of excellence. How to win in sport and life through mental training. Champaign: Leisurepress

- Orlick, (2007). Mental training, how to win in sport and life thanks to mental activity. Barcelona: Paidotrivo.

- Paradis, K, Martin, L, Carron, A, (2012). We are examining the relationship between passion and perceptions of cohesion in athletes, Sport and Exercise Psychology Review (8), 22-31.

- Pérez Marván L. (2005) Manual of Normal and Therapeutic Diets, Coyoacán Scientific Editions

- Perreaut E. (2000). Sophrology and sports success. Barcelona, Paidotrivo. Sommer B, Sommer (2001) Behavioral Research Mexico Oxford

- Viade, (2003). Psychology of sports performance. Barcelona: UOC.

- Wicks-Nelson, Allen C, I. (1997). Child and adolescent psychopathology. Madrid: Prentice Hall.

- Williams, M. (2002). Nutrition: for health, fitness, and sport. Barcelona: Paidotrivo. Zhelyastov (2001) Bases of sports training. Barcelona: Paidotribo