Article / Research Article

Aquatic Contaminants Research Division, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 105 McGill, Montréal, Qc, Canada H2Y 2E7.

François Gagné,

Aquatic Contaminants Research Division,

Environment and Climate Change Canada, 105 McGill, Montréal, Qc,

Canada H2Y 2E7.

17 November 2025 ; 11 December 2025

The increasing demands on our water resources require the rapid evaluation of water quality of surface waters near urban areas. The purpose of this study was to examine urban surface waters by rapid and cheap two biochemical-based assays: the peroxidase toxicity (Perotox) test and the prebiotic pyruvate-glyoxalate (pyr-glyox) pathway for malate synthesis. Surface waters samples were extracted on C18 solid phase cartridge and eluted with ethanol. The evaluation of plastic polymers was also determined as a proxy of water pollution. The data revealed that plastic materials were found in both small and large urban areas and were lower downstream a municipal treated effluent. The prebiotic assay for malate production was significantly blocked by water extracts for the most populated city (1.8 million population) and in the corresponding municipal effluent dispersion plume. For the Perotox assay, the same results were obtained for the surface water extracts. An add-on of the Perotox assay included a DNA protection index for the detection of potential genotoxic compounds. The DNA protection index was significantly increased at the most populated city and was lost in the treated municipal effluent dispersion plume. In conclusion, two highly sensitive biochemical assays are presented to quickly monitor changes in water quality from urban pollution where stronger impacts were found from highly populated cities and in some case in the corresponding wastewater dispersion plume.

Keywords: Surface water quality assessment, peroxidase, malate production, probiotic chemistry, plastic pollution.

The release of contaminants from urban, agricultural and industrial activities including street runoffs contributes to decreased water quality compromising aquatic ecosystem integrity. These effluents are complex mixtures containing a plethora of xenobiotics such as heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, miscellaneous plastic polymers, pesticides, endocrine disruptors (estrogen mimicking compounds) and aromatic hydrocarbons (Holeton et al., 2011; Samal et al., 2023; Zdarta & Li 2025). Moreover, these mixtures contain also unknown compounds identified by non-targeted approaches and have yet to be fully characterized for their ecotoxicological properties (McLachlan et al., 2022). By using direct injection UHPLC-orbitrap-MS/MS technology with a library of 7000 compounds, the removal of 293 breakthrough chemicals in 15 wastewater treatment plant using various water treatment processes were determined. These chemicals were found to significantly follow total suspended solid and the biochemical oxygen demands. Hence, the need to screen the water quality of surface waters impacted by wastewaters and urban/agriculture runoffs using cost-effective means for research, monitoring and regulatory purposes. In an ideal world these tools should be simple, quick and cheap without compromising the ecotoxicological (effects) information (Blaise et al., 1991). For example, the bioluminescent marine bacteria Vibrio fisheri, the SOS chromotest in Escherichia coli for toxicity and genotoxicity assessments are well known microbiotests with sufficient sensitivity for surface waters (Quillardet & Hofnung, 1993; White & Rasmussen, 1998). The continuous search for faster and sensitive biotests is nevertheless an on-going goal in the context of new and emerging chemicals of interest such as nanomaterials, micro/nanoplastics and their polymers and high technology materials (rare earth, ionic liquids etc.). Enzymes and metabolic pathways could be used as sensors instead of organisms to determine surface water quality impacts by xenobiotics. For example, the peroxidase toxicity (Perotox) has been proposed as a simple, quick (requiring 5 min incubation times) and cheap tool to assess water quality (Gagné & Blaise, 1997; Ilyana et al., 2000; André et al., 2025). The preincubation with herbicides, detergents, metals, surfactants and bactericides led to peroxidase inhibitions. Inhibitions of peroxidase activity leading to sustained levels of H2O2 were shown to follow chemical (Groele & Foster, 2019) and falsely lowers biochemical oxygen demands of wastewaters. The Perotox assay was practiced on various industrial/municipal effluents and compared with bacterial luminescent, rainbow acute lethality and Ceriodaphnia dubia survival and reproduction tests (Gagné & Blaise, 1997). Over the 21 industrial effluents examined, peroxidase inhibition was associated to toxicity with at least of one of the above tests and showed good correspondence with the acute trout lethality results. The protective effects of exogenous DNA in protecting peroxidase inhibitions successfully identifies genotoxic effluents in 70% of tested effluents as determined by the SOS chromotest. More recently, the prebiotic pyruvate and glyoxylate (pyr-glyox) pathway for the formation of malate and oxaloacetate has been proposed as an alternative testing method for toxicity assessment (Gagné & André, 2025). The principle of this assay resides in the notion that inhibition of ancient biochemical reactions found in all life forms could provide early insights on toxicity initiation. This biochemical test is surprisingly simple and quick requiring a 2 h incubation time of the test sample with pyr, glyox in the presence of reduced iron (Fe2+). This prebiotic metabolic pathway was tested on 11 compounds where the inhibitory concentrations were correlated with the rainbow trou acute lethality tests. This study revealed that not only oxidant compounds could initiate toxicity but compounds disrupting aldol condensation and dehydration reactions as well.

The purpose of this study was therefore to examine the surface water quality and potential toxicity of surface waters collected at urban sites of increasing population size. The surface water samples were tested on the above-described biochemical tests: the Perotox and pyr-glyox pathway for malate formation. In parallel, surface water basic characteristics and plastic polymers were determined as markers of exposures to environmental pollutants from urban cities. An attempt was made to determine the influence of population size and wastewater treatment of the largest city towards surface water indicators including the occurrence of potentially genotoxic compounds.

Surface Water Collection and Preparation

Surface waters and “wastewaters” 1km downstream the discharge point were collected as grab samples (3 x 1L) at 5 sites. The surface waters were collected in the Saint-Lawrence near 4 cities of increasing population size as shown in Table 1. For city 1, the water samples were collected at the city of Lavaltrie pier (Latitude: 45.874418; Longitude: -73.280645), while at cities 2 and 3, the water samples were collected at the mouth of each of Chateaughay (Latitude 45.37688; Longitude -73.751142)/Rivière du Loups (Latitude: 47.847111; longitude: -69.538) rivers and the Saint-Lawrence River respectively. For City 3, the river water sample was discharged in the marine part of the Saint-Lawrence river/estuary. For the largest city 4 (city of Montreal), a water sample was taken at 20 km downstream the city centre (City 4; Latitude: 45.6588; longitude: -73.47736) before the municipal effluent discharge point and one sample 1 km downstream the municipal effluent dispersion plume (City 4E; Latitude 45.67451; Longitude: -73.45916). Standard water parameters (pH, conductivity, chlorophyll a) were determined using standard operational procedures (AWWA, 2017). A 200 mL sample was collected in glass 1 L bottles, brought to the laboratory at 4oC, filtered on 0.8 µm cellulose acetate membrane for the removal suspended solids. The filtrate was then passed through a C18 solid phase extraction cartridge (Bond Elut, 100 mg bed mass), washed with 5 mL of MilliQ water and eluted with 1 mL analytical grade ethanol. The ethanol extracts corresponding to 200 X concentration were kept at 4oC until analysis the same week. Operational ethanol blanks and MilliQ water in bottle were included.

The levels of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the C18 ethanol extracts were determined by the UV spectroscopic method (Brandsetter et al., 1996). The absorbance was measured at 254 nm and the linear relationship between DOC and concentration in mg/L was used in obtained the DOC. The levels of plastic nanoparticles were determined using the plasmonic nanogold methodology (Zhou et al., 2023). Citrate-coated nanogold (10 mg/mL in 1% citrate buffer, 10 nm diameter, Polyscience) were centrifuged at 20 000 x g form 10 min and resuspended in 0.1% mercaptoundecanoic (MUA) acid overnight at 4oC. The suspension was centrifuged again and resuspended in MilliQ water yielding MUA-coated nAu. The assay consisted in adding 10 µL of C18 ethanol extract of surface waters (200 X) to 120 µL MUA-coated nanogold for 5 min. HCl was added at a final concentration of 10 mM to initiate aggregation of nAu-MUA (blue color, absorbance 620 nm) from the initial pink red (absorbance at 530 nm). A characteristic decrease at 620 nm with an increase at 570 nm is observed in the presence of plastic nanoparticles. Standard solution of polystyrene nanoparticles (20 nm diameter, Thermofisher, Canada) was used for calibration. The presence of plastic polymers (polypropylene, and polyvinyl chloride/polystyrene) in the DOC matrix was determined using the copper (Cu)-quenching fluorescence methodology (Lee et al., 2021). This spectral methodology determines plastic polymers in the dissolved organic matrix and is not restricted to the size range of 10-100 nm nanoparticles as with the MUA-nAu methodology. The Cu-induced decreases in fluorescence for humic/fulvic acids (HA/FA) was determined in 10 % final ethanol concentration of the C18 extract or the blank at 265 nm excitation/463 nm emission and normalized to the DOC contents. Polypropylene (PP)-derived materials and polyvinyl chloride /polystyrene-derived materials were determined at 250 nm excitation/324 nm emission and 295 nm excitation/411 nm emission respectively before and after the addition of 20 µM of CuCl2 (prepared in 10% ethanol). The difference between fluorescence without Cu – fluorescence with Cu was calculated and standard solutions of polystyrene (PS; 20 nm diameter) and polypropylene (PP; 100 nm diameter) was used for validation. The data were expressed as µg PP or PS/PVC-equivalents/ mg DOC.

The potential toxicity of surface water extracts was determined using 2 biochemical assays previously shown associated to fish toxicity. These assays consist of the Perotox and the prebiotic pyruvate (pyr) and glyoxylate (glyox) assays (Gagné & Blaise, 1997; Gagné & André, 2025). For the Perotox assay increasing concentrations of the ethanol extracts (20 µL; 0.8, 4 and 20 X) were mixed with 170 µL of the Perotox reagent (1 µg/mL peroxidase, 1 µg/mL albumin, 0.1% H2O2 in phosphate buffered saline (140 mM NaCl, 1 mM KH2PO4 and 1 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.4.) for 5 min. The reaction was started by the addition of 10 µL of dicholorofluorescin (2 µM) and readings at 485 nm excitation and 520 nm emission and absorbance at 418 nm for the peroxidase intermediate III were taken at each 2 min for 30 min. The assay was also determined in the presence of 10 µg/mL salmon DNA to determine potential genotoxic compounds. The DNA protection index (DNAI) was calculated by peroxidase rate with added DNA/peroxidase rate without DNA. For the pyr-glyox pathway leading to formation of malate, increasing concentrations of C18 extracts (100 µL) were added to 0.9 mL of the reaction mix (1 mM pyr, 2 mM glyox and 4 mM FeSO4) and incubated at 70oC for 2-3 h. At the end of the exposure period, the levels of malate were determined using the malate dehydrogenase assay as previously described (Beeckmans & Kanarek, 1981). Briefly, 10 µL of the above was mixed with 190 µL of 10 units of malate dehydrogenase, 100 mM NaCl containing 10 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM NaHCO3 and 0.1 mM NAD+. The appearance of reduced NADH was monitored in dark microplates at 350 nm excitation and 450 nm emission at 3 min interval for 20 min. The data are expressed as malate equivalents in relative fluorescence units (RFU/min).

Surface water samples were collected in triplicate (N=3) 1 L sample in glass bottles. Each replicate water sample was tested in duplicate for the Perotox and pyr-glyox assays. The data was analyzed by Kruskall-Wallis analysis of variance using the Conover-Iman test to highlight changes from controls. Correlation analysis was also performed using the Pearson-moment procedure. Discriminant function analysis was performed to determine which surface waters parameters achieved city discrimination based on population differences. Significance was set at p<0.05 and all tests were performed by the Statsoft software package (US).

The surface water samples were collected in the vicinity of 4 cities with increasing population size and the municipal dispersion plume of the largest city 4 (Table 1). The population size range was between 14425 to 1.8 million inhabitants. The pH range was between 7.5 to 8.1 with no clear influence of city (population) size. The DOC measured in the C18 extracts were slightly elevated at cities 3 and 4E, which was located downstream the municipal effluent plume for the latter. Chla contents were variable and showed a biphasic change albeit not at significance. Compared to city 1, chla was lower for city 4 and its municipal dispersion plume city4E and higher at city 3, located at the south shore of the Saint-Lawrence river receiving the input of green waters from lake Ontario.

Table 1: Site identification and water quality parameters.

| Townships | Population | WWT1 | pH/conductivity2 | DOC (mg/L) | ChlorophyllA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City 1 (LA) | 14425 | Aeration lagoons |

7.5±0.4 150±25 |

1.4±0.01 | 2.9±1 |

| City 2 (RDP) | 20475 | Advanced Aeration lagoons |

8.0±0.3 20000 ± 6000 (marine) |

1.5±0.02 | Nd |

| City 3 (CHE) | 50815 | Biofiltration | 8.1±0.5 261±30 |

1.3±0.01 | 6.3±3 |

| City 4 (Mtl Pylone) | 1800000 | Physico-Chemical treatments/Primary | 7.8±0.4 270±30 |

1.42±0.01 | 1.6±1 |

| City4E (IST) | idem | 7.7±0.5 330±50 |

1.5±0.03 | 1.7±1 |

1. Wastewater treatment; 2. Conductivity expressed in µScm-1.

The surface water extracts were further examined for levels of plastic nanoparticles (PSNPs) and plastic polymers of PVC, PP, PS and humic/fulvic acids in the C18 extracts (Table 2). The levels of PSNPs were significantly higher in cities 1, 2 and 4 compared to the municipal effluent dispersion plume (City 4E), known to contain less plastic materials in previous studies (André et al., 2025). The values ranged from 2 to 3.5 µg PSNPs /mg DOC in the surface waters. The levels of PVC/PS and PP polymers were determined by the Cu-quenching fluorescence methodology revealed a decrease in PVC/PS at city 3 located in marine waters in the Saint Lawrence estuary (Table 2). The levels of PP polymers were lower for cities 3 and 4 and higher at city 1 compared to city 4E (1 km downstream the plume). Humic/fulvic acids were significantly higher at city 4 site as expected since the waters is mostly composed of organic rich brown waters on the north shore of the Saint-Lawrence river. Correlation analysis revealed that the PSNPs was negatively correlated with population size (r=-0.62) and humic/fulvic acids (r=-0.84). This suggests that sites from low population sites contain less humic/fulvic acids and more plastic nanoparticles.

Table 2: Plastic materials in surface water extracts.

| Townships | PSNPs (µg/mg OC) | PVC/PS (µg/mg OC) | PP (µg/mg OC) | Humic/fulvic Acids (RFU/mg OC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| City 1 (LA) | 3.42±0.08* | 4.8±2 | 9.6±2* | 0.48±0.06 |

| City 2 (RDP) | 2.69±0.12 | 0.71±0.25* | 2.2±0.5* | 0.8±0.06 |

| City 3 (CHE) | 3.1±0.2* | 5.1±3 | 8.5±2 | 0.45±0.06 |

| City 4 (Mtl Pylone) | 3.05±0.06* | 2.9±1.8 | 2.7+0.7* | 8.7±2* |

| City4E (IST) | 2.03±0.04 | 4.5±0.6 | 6±1.5 | 0.24±0.1 |

*significant relative to the City4E.

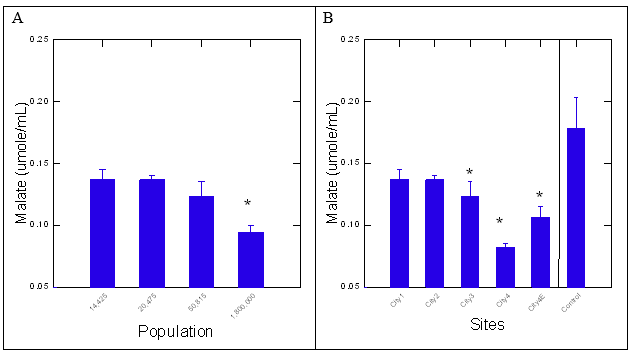

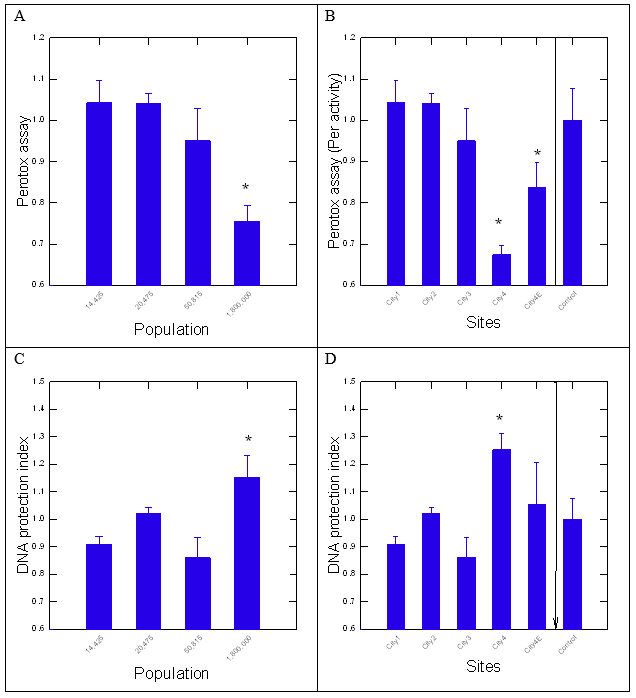

The quality of the surface water extracts was examined by biomolecular and enzyme-based assays. For the pyr-glyox assay, the formation of malate was significantly lower at the most populated city (City 4) and its municipal dispersion plume (City 4E) suggesting degraded water quality (Figure 1A and 1B). Malate production was also significantly dampened at City 3 compared to control blanks (ethanol). Correlation analysis revealed that population size was the main driver of changes; population was correlated with malate levels (r=-0.84 and to Perotox assay at r=-0.67), PsNPs (r=-0.62), humic/fulvic acid (r=0.54) and Chla (r=-0.7). This suggests that highly populated cities inhibit more strongly malate levels and contain more Chla with lower humic/fulvic acid and PSNPs. Indeed, PSNPs was rather associate to lower population size and did not significantly contribute to lower water quality at the most populated city 4. Hence, water quality decreases at a threshold population of 300 600 inhabitants (geometric mean of city 4 and city 3 = [1800000 x 50815] ½). Water quality was further examined by the Perotox assay and revealed similar findings. The assay determines peroxidase inhibitions by the surface water extracts without and with added DNA. Peroxidase activity was significantly inhibited by the surface waters from the most populated city and its municipal dispersion plume (city 4E), in concordance with the pyr-glyox pathway assay (Figure 2A and 2B). The levels of intermediate III of peroxidase, representing a non-catalytic state for removing H2O2, did not significantly change with(out) the addition of DNA (results not shown). Correlation analysis revealed that the Perotox assay was correlated with the pyr-glyox assay (r=0.5), population size (r=-0.67) and PSNPs (r=0.74). Again, this suggest that PSNPs contribute less to water quality as defined by both the pyr-glyox and Perotox assays. A variation of the Perotox assay consists of pre-incubation of a fixed quantity of DNA with the extract to seek out whether peroxidase inhibitions could be prevented by DNA. The DNA protection index-DNAi (ratio of peroxidase activity with(out) added DNA) was significantly higher for surface waters collected at the most populated city (Figure 2C). The DNAi was significantly higher at the most populated city but not in the municipal dispersion plume indicating reduced output of genotoxic compounds. This suggests that genotoxic compounds are released by a population threshold of 300600 inhabitants in the Saint-Lawrence river. The DNAi was significantly correlated with population (r=0.56), PSNPs (r=-0.73), humic/fulvic acid (r=0.52), pyr-glyox (r=-0.48) and Perotox (r=-0.77) assays.

Figure 1: Inhibition of malate formation by surface waters with the pyr-glyox assay.

Figure 1: Inhibition of malate formation by surface waters with the pyr-glyox assay.

Surface water extracts were examined with the pyr-glyox assay at 20X final concentration. The data represent the mean levels of formed malate with the standard deviation. The star symbol * indicates significance against control (A) and lowest populated city – 14425 inhabitants (B).

Figure 2: Surface water assessment with the Perotox assay and DNA protection index.

Figure 2: Surface water assessment with the Perotox assay and DNA protection index.

Surface water extracts were examined with the pyr-glyox assay at 20X final concentration. The data represent the mean levels of formed malate with the standard deviation. The star symbol * indicates significance towards the lowest populated sector – 14425 inhabitants (A, C) and solvent control (B, D)

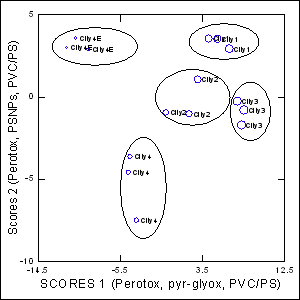

In the attempt to gain a global view of the surface water characteristics, a discriminant function analysis was conducted (Figure 3). The analysis revealed that all cities and the municipal dispersion plume of city 4E were separated with a total explained variance of 97% with the 2 scores. The global properties of cities 1, 2 and 3 were more closely related than the largest city 4 and its corresponding municipal effluent dispersion plume (city 4E). Moreover, the municipal dispersion plume waters also markedly differed from the surface waters downstream city 4 indicating that the wastewater treatment readily changed the properties the surface waters in this sector. The analysis also revealed that Perotox, pyr-glyox assays, PSNPs and PVC/PS polymers were the most important properties for surface water discrimination between the sites.

Figure 3: Discriminant function analysis of surface water characteristics.

Figure 3: Discriminant function analysis of surface water characteristics.

Discriminant was determined with the various parameters to determine similarities between sites (cities) and determine the most important descriptors allowing site discrimination. The analysis revealed that the total variance was explained at 97%, all cities including the municipal effluent plume were completely discriminated and the most important properties are listed on the abscissa and ordinate scales: Perotox, pyr-glyox, PVC/PS and PSNPs.

In this study, the two biochemical-based markers of water quality (pyr-glyox and Perotox) revealed a similar pattern of response from 4 cities including the municipal dispersion plume of the most populated city. This result is particularly of interest given that these assays were able to predict fish mortality and currently proposed as fish alternatives the reduce fish use for monitoring surface waters (Gagné & André. 2025). However, the observed responses occurred at 20 X concentration of the extracts indicating that direct toxicity effects in undiluted waters are unlikely. A previous study with the pyr-glyox assay revealed that toxic effects of city 4 were possible since malate decreases were observed at concentration <1 X (Gagné & André, 2025). Another study with caged freshwater mussels revealed surface waters contaminated by municipal wastewater can reduce survival (mortality) following 30 days exposure at 0.2 km downstream a municipal effluent dispersion plume of 2 tertiary treated municipal effluents in the Saint-Lawrence River on the north shore of Montreal (Bouchard et al., 2009). These assays could be used to identify polluted sites likely to elicit toxicity in a preventive manner i.e., before the onset of toxicity manifestations. The levels of PSNPs were elevated at both the lowest and highest population city suggesting other variables. High plastic levels from low populated cities were previously observed and may reflect the ability of some wastewater treatment systems to generate/release plastic nanomaterials (André et al., 2025). Indeed, low population cities often use aeration lagoons where small plastic debris (nanoparticle) could remain in suspension or from the release of nanoplastics from larger particles because of high residency times of wastewaters in lagoons. Typically, aeration ponds have longer residency times (mean of 25 days) over primary physico-chemical treated effluents with residency times of min to h (Calabro et al., 2024). The levels of PS in the organic fraction of effluents were higher in a primary aerated lagoons usually used in small population townships compared to other more sophisticated treatment processes for larger populations (André et al., 2025). They also found a negative correlation between peroxidase inhibitions and plastic materials indicating that while effluents from smaller cities are less toxic (Perotox assay), they still release high levels of plastics. Municipal effluents have the capacity to remove plastic materials (< 1 um) from the water column compared to untreated wastewaters at various degrees (Okoffo & Thomas, 2024). This could explain why treated municipal effluents (city 4E; low residency times) showed lower plastic contents compared to surface water downstream large cities in the present study. For example, the total nanoplastic removal rates were between 91 to 96% from three wastewater treatment plants (Okoffo & Thomas, 2024). Nanoplastics were found in all city sizes (320,000, 30,000, and 13,000) where plastic loadings in released effluents followed population size but these values could change depending on the type of wastewater treatment as discussed above. In the present study, city 4E used an advance physico-chemical treatment with Alun/phosphate precipitation steps for the removal of suspended matter but at low residency times. However, the capture and breakdown of plastic materials in municipal effluents could release smaller size plastic nanomaterials which could change the size distribution of plastics in effluents (Zdarta & Li, 2025). The quantity of plastics entering the wastewater treatment plants depends on many factors such as street runoffs capture, city area, population and treatment processes. Primary treatment processes involve MP fragmentation by mechanical interactions, chlorination, and the presence of oxidation processes while aeration ponds involve less stringent mechanical stress albeit with longer residency time permitting the release of small plastic nanoparticles and organic matter in the water column. Aeration lagoons (sedimentation and biological/biofilm degradation) were less efficient in removing microplastics (and perhaps nanoplastics) than more advanced treatment systems using tertiary treatments (Xiao et al. 2025). However, surface waters were collected at the river (not the effluents) where the release of plastic materials could stem from solid waster and street runoffs as well. These pathways were also recognized as entry of nanoparticles for the aquatic environment (Wang et al., 2025).

The relationships between chla, PSNPs and Perotox/malate assays could imply that plastic nanomaterials enter the environment by absorption in algae/cyanobacteria from the water column forming the base of food webs. This could represent a moving “sink” of plastics compared to fixed biofilms at the sediment/water interface. Biofilms were shown to accumulate plastics in their gel-like matrix or directly formed on plastic materials (coined as the plastisphere) (Ge & Lu, 2023). A recent study revealed that MP and NP found in surface water are unlikely to produce direct toxic effects to phytoplankton (Yang et al., 2025). However, sublethal impacts on photosynthesis and ribosome pathways were reported where detoxification mechanisms involved alanine, aspartate, glutamate and purine metabolism. The increase in purine metabolism could be the result of increased DNA turnover from oxidatively damaged nucleotides or DNA-adducts. This is consistent to the close (and significant) association between PVC-PS polymers and DNAi in the present study. A recent study showed that nanoplastics absorb to microalga making this an eco-friendly plastic removal strategy (Li et al., 2025). However, exposure of small PS (1 µm and 100 nm) inhibited growth and photosynthesis and increased the production of reactive oxygen species in Microcystis aeruginosa (Wu et al., 2021).

The increase in DNAi with population, PVCPS and Hum/fulvic acids indicates that the presence of genotoxic compounds at the downstream from the city 4 (City of Montréal, Qc, Canada). The DNAi was able to predict genotoxic effluents towards bacteria in 70% of times (Gagné & Blaise, 1997). The DNAi of the municipal effluent (City 4E) were somewhat higher but was not significant owing to higher variance. In a previous study, the DNAi was significantly increased in a primary treated effluent of similar city size (Gagné et al., 2025), which was obtained from a 3 day composite sample of the effluent (in the present study it was grab samples). Notwithstanding, the release of genotoxic compounds from the city of Montreal (City 4) was already known (White & Rasmussen, 1998). The genotoxicity was determined in surface water extracts and mass balance analysis of water genotoxicity revealed that 85% of the total genotoxicity contributions from the Montreal area were of domestic origin. The study also revealed a significant relationship between population and genotoxicity potential. This corroborates our finding that the DNAi was significantly higher in the highly populated city 4. The genotoxicity (mutagenicity) of C18 extracts of various industrial effluents were described in Salmonella typhimurium assay (Bobeldijk et al. 2001). Genotoxicity was detected in 10 fractions of C18 chromatographic elution fractions (total fractions 45) of industrial effluents while only one more polar fraction than those for the industrial effluent fractions were genotoxic. However, over 15-20 elution fractions were genotoxic to the bacteria from hospital wastewaters.

In conclusion, the surface waters from different population area were collected in the Saint-Lawrence river and water quality assessed by two biochemical assays. These rapid and inexpensive assays were able and concordant to determine the impacts of population size on reduced water quality. The influence of municipal dispersion plume was also examined and could mitigate impacts of urban pollution towards water quality. Plastic materials were ubiquitous in surface waters and did not follow population size. Biochemical-based assays to monitor changes in water quality and ecotoxicity represent inexpensive and quick methods to identify areas at risk of pollution in a preventive manner.

The surface water collection was performed by Maxime Gauthier and Edith Lacroix from the. Water Quality Monitoring Section, Environment and Climate Change Canada. The authors thank the technical assistance of Hibah Qchiqach for the preparation of surface water extracts.

- Holeton, C., Chambers, P. A., Grace, L., & Kidd, K. (2011).Wastewater release and its impacts on Canadian waters. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci, 68(10), 1836-59. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1139/f2011-096

- Samal, K., Mahapatra, S., & Ali, M. H. (2022). Pharmaceutical wastewater as Emerging Contaminants (EC): Treatment technologies, impact on environment and human health. Energy Nexus, 6(16), 100076. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100076

- Zdarta, A., Li, G. (2025). The Paradox of Microplastic Removal in WWTP: Redistribution of Micropollutants in the Environment. Current Pollution Reports, 11(30), DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-025-00370-w

- McLachlan, M. S., Li, Z., Jonsson, L., Kaserzon, S., O’Brien, J. W., & Mueller, J. F. (2022). Removal of 293 organic compounds in 15 WWTPs studied with non-targeted suspect screening. Environ. Sci: Water Res & Technol, 8, 1423-1433. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D2EW00088A

- Blaise, C. (1991). Microbiotests in aquatic ecotoxicology: Characteristics, utility and prospects. Environ Toxicol. Water Qual, 6(2), 145-155.

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1002/tox.2530060204 - Quillardet, P., & Hofnung, M. (1993). The SOS Chromotest: A review. Mutat. Res, 297(3), 235-279. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1110(93)90019-j

- White, P. A., & Rasmussen, J. B. (1998). The genotoxic hazards of domestic wastes in surface waters. Mutat Res, 410(3), 223-236.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1383-5742(98)00002-7 - Gagné, F., & Blaise, C. (1997). Evaluation of industrial wastewater quality with a chemiluminescent peroxidase activity assay. Environ Toxicol Water Qual, 12(4), 315-320. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2256(1997)12:4%3C315::AID-TOX5%3E3.0.CO;2-B

- Ilyina, A. D., Hernandez, J. L. M., Lujan, B. H. L., Benavides, J. E. M., Garcia, J. R. & Martinez, J. R. (2000). Water Quality Monitoring Using an Enhanced Chemiluminescent Assay Based on Peroxidase-Catalyzed Peroxidation of Luminol. Appl Biochem Biotechn, 88(1), 45-58.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1385/ABAB:88:1-3:045 - André, C., Smyth, S. A., & Gagné, F. (2025). The peroxidase toxicity assay for the rapid evaluation of municipal effluent quality. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics, 4, 2. https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/wecn.2024.63

- Groele, J., & Foster, J. (2019). Hydrogen Peroxide Interference in Chemical Oxygen Demand Assessments of Plasma Treated Waters. Plasma, 2(3), 294-302. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/plasma2030021

- AWWA, (2017). Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, (23rd edition). American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Environment Federation. https://yabesh.ir/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Standard-Methods-23rd-Perv.pdf

- Brandstetter, A., Sletten, R. S., Mentler, A., & Wenzel, W. W. (1996). Estimating dissolved organic carbon in natural waters by UV absorbance (254 nm). Pflanrenernahr. Bodenk, 159. 605-607.

DOI: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/link_gateway/1996ZPflD.159..605B/doi:10.1002/jpln.1996.3581590612 - Zhou, H., Cai, W., Li, J., & Wu, D. (2023). Visual monitoring of polystyrene nanoplastics < 100 nm in drinking water based on functionalized gold nanoparticles. Sensors & Actuators: B. Chem, 392, 134099. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2023.134099

- Lee, Y. K., Hong, S., & Hur, J. (2021). Copper-binding properties of microplastic-derived dissolved organic matter revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy and two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Water Res, 190, 116775. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116775

- Gagné F., & André, C. (2025). The pyruvate-glyoxalate pathway as an alternative toxicity assessment tool of xenobiotics: lessons from prebiotic chemistry. J. Xenobiot.15, 198.

- Beeckmans, S., & Kanarek, L., (1981). Demonstration of physical interactions between consecutive enzymes of the citric acid cycle and of the aspartate-malate shuttle. A study involving fumarase, malate dehydrogenase, citrate synthesis and aspartate aminotransferase. Eur J Biochem, 117, 527-535, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb06369.x

- Bouchard, B., Gagné, F., Fortier, M., & Fournier, M. (2009). An in-situ study of the impacts of urban wastewater on the immune and reproductive systems of the freshwater mussel Elliptio complanatae. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol, 150(2), 132-140.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.04.002 - Calabrò, P. S., Pangallo, D., & Zema, D. A. (2024). Wastewater treatment in lagoons: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Environ Manag, 359, 120974. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120974

- Okoffo, E. D., & Thomas, K.V. (2024). Mass quantification of nanoplastics at wastewater treatment plants by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Water Research, 254(1), 121397. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2024.121397

- Xiao, Z., Feng, Y., Qian, H., Li, S., & Yu, H. (2025). Microplastic Removal Efficiency of Four Wastewater Treatment Processes in Kunming: Mechanisms and Optimal Process Selection. Environ Manage, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-025-02280-5

- Wang, C., O’Connor, D., Wang, L., Wu, W-M., Luo, J., & Hou, D. (2025). Microplastics in urban runoff: Global occurrence and fate. Water Res, 225(15), 119129. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119129

- Ge, Z., & Lu, X. (2023). Impacts of extracellular polymeric substances on the behaviors of micro/nanoplastics in the water environment. Environ Pollut, 338, 122691. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122691

- Yang, W., Gao, P., Ye, Z., Chen, F., Zhu, L. (2024). Micro/nano-plastics and microalgae in aquatic environment: Influence factor, interaction, and molecular mechanisms. Sci Total Environ, 934, 173218. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173218

- Li, R., Karimi, J., Wang, B., Liu, Y., & Xie, S. (2025). A brief overview of the interaction between micro/nanoplastics and algae. Biologia, 80, 201–213. DOI: 213 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11756-024-01839-7.

- Wu, D., Wang, T., Wang, J., Jiang, L., Yin, Y., & Guo, H. (2021) Size-dependent toxic effects of polystyrene microplastic exposure on Microcystis aeruginosa growth and microcystin production. Sci Total Environ, 761(20), 143265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143265.

- Gagné, F., Roubeau Dumont, E., & André, C. (2025). The effects of selected metals and rare earth elements on the peroxidase toxicity assay. Adv Earth & Env Sci, 6(3), 1 – 8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.47485/2766-2624.1069

- Bobeldijk, I., Brandt, A., Wullings, B., & Noij, T. (2001). High-performance liquid chromatography–ToxPrint: chromatographic analysis with a novel (geno)toxicity detection. J Chromatogr A, 918(2), 277-291. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(01)00756-7