Article / Case Study

1Research Institute for water management end climate future at the RWTH Aachen university, Germany,

2University of Frankfurt/M, Germany.

Henry Risse,

Research Institute for water management end climate future at the RWTH Aachen university,

Germany.

27 November 2025 ; 12 December 2025

The success of the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energies depends significantly on storage capacities. The decommissioning of coal-fired power plants in Germany over the next ten years will lead to a supply deficit of 30 to 40 GW at night without wind power. On sunny days, however, a surplus of photovoltaic electricity of over 50 GW is already expected and will continue to be expected in the near future. The traditional technology for storing large amounts of electricity is pumped storage. This robust technology has a service life of approximately 100 years, compared to batteries with approximately 20 years. However, there are very few available and approved sites for new pumped storage power plants in Germany. Therefore, alternative locations must be found.

This article describes a new approach that proposes using existing, old open-cast lignite mines as sites for new pumped storage power plants. In the Renish mining district – a region between Cologne, Erkelenz, and Aachen – three large open-cast lignite mines are currently in operation, but these will be decommissioned in the coming years. The open-cast lignite mines reach depths of between 200 and 400 meters, thus offering ideal conditions for pumped-storage power plants. The Hambach mine, in particular, with its 400-meter depth, is exceptionally well-suited for such an unconventional pumped-storage power plant. A key feature is the separation of the water volume between the upper and lower storage basins from the residual water in the retention basins. The lower storage basin can be constructed in large, reinforced concrete caverns with a diameter of over 60 meters. The upper storage basin is located near the former ground level. The Hambach site allows for the installation of a capacity exceeding 6 GW and a storage capacity of over 50 GWh, which would surpass the maximum output of the largest pumped-storage power plant in Germany by at least five times. This Hambach pumped-storage power plant could cover a large portion of Germany’s total storage demand during the day-night cycle.

Photovoltaics and wind energy play a central role in Germany’s energy transition. However, their growing share of electricity generation is causing increasingly pronounced grid fluctuations. Therefore, the short-term storage of renewable electrical energy for periods ranging from hours to a few days is crucial for the success of the energy transition. Currently, however, this remains an unresolved problem.

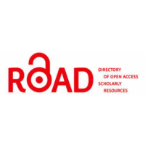

While wind power depends on position of low-pressure athmospheric systems and the course of the jet stream, the further expansion of photovoltaics in electricity generation is expected to lead to enormous fluctuations between day and night. As Figure 1 clearly shows, daytime surpluses will exceed 70 GW and 500 million kWh on many days, while at night there will be a deficit of several hundred million kWh. Photovoltaics, in particular, will be responsible for these large surpluses.

Figure 1: Forecast of electricity generation and demand in Germany in the near future (Bundesnetzagentur, (n.d)).

Figure 1: Forecast of electricity generation and demand in Germany in the near future (Bundesnetzagentur, (n.d)).

The red curve in Figure 1 describes the future total electricity consumption of industry and households in gigawatts (Bundesnetzagentur, (n.d)), while the black curve represents the sum of wind energy and wind power generation. These curves are generated from the real data of the week from April 12th to 18th in 2021 and the black curve was multiplied by a factor of approximately 4. This corresponds approximately to the expansion target for all of Germany. The yellow areas indicate daytime surpluses, the blue areas night time deficits.

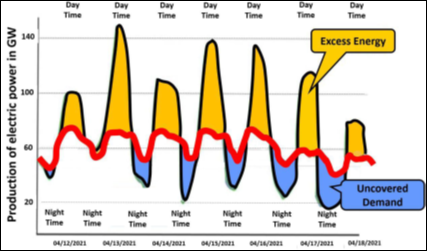

In addition, the large fluctuations in electricity generation (surplus and deficit) cause significant problems in the high-voltage grid. The following diagram shows the forecasts for power curtailments over the course of the year depending on different photovoltaic production expansion scenarios with timeline until 2045.

Figure 2: Scenarios of PV curtailments over the course of a year with insufficient storage capacity (Bewertung Systemstabilitätsbericht Bundesnetzagentur, 2025).

Figure 2: Scenarios of PV curtailments over the course of a year with insufficient storage capacity (Bewertung Systemstabilitätsbericht Bundesnetzagentur, 2025).

When it comes to storing electrical energy on a large scale, the fundamental question arises as to which storage concepts are best suited and what additional requirements they must meet. First, a distinction must be made between short-term and long-term storage. Large long-term storage systems for bridging extended periods of low wind and low solar irradiance can only store electricity by converting it into chemical energy, i.e., synthetic methane, methanol, biomethane, or hydrogen.

However, this article focuses primarily on storage for a few hours or days to compensate for fluctuations between day and night. Such short-term storage systems must be able to convert and store a total of several tens of gigawatts of electrical power within a typical 10-hour period. This corresponds to energy amounts of several hundred gigawatt-hours, and the conversion efficiency should ideally exceed 80%. Furthermore, the raw materials required for manufacturing the storage facilities should be environmentally friendly and, if possible, available in Germany. The necessary technology should be technically mature and have a very long lifespan. Last but not least, storage costs, and therefore costs for industry and the public, must be affordable.

Currently, the following three storage technologies are being discussed: conversion to green hydrogen, lithium/sodium-ion batteries, and pumped-storage hydroelectric plants. Electricity-to-hydrogen conversion is currently used in small and medium-sized plants and is a solution for long-term storage. However, the efficiency of reconversion to electricity is very low. Electrolysis systems using PEM require rare elements such as iridium and ruthenium, which are very expensive and are currently entirely used in other (chemical) processes.

Electrochemical storage systems (lithium-ion batteries) are currently the preferred solution for storing surplus electricity. Their costs have fallen significantly, and they are now also being used on a large scale (>100 MWh). However, battery production also requires highly limited raw materials (lithium, nickel, cobalt). With increasing global demand for batteries in cars, buses, and trains, these elements could represent a bottleneck in meeting the significantly increased demand.

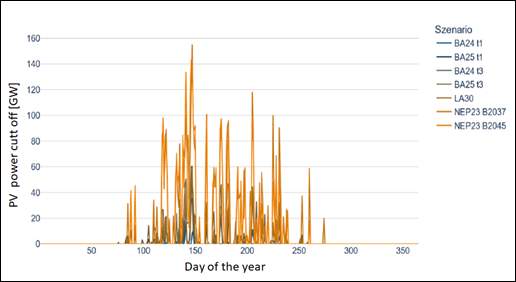

The third storage technology – pumped-storage hydroelectric plants – is a proven system with very long lifecycles of up to 100 years. They deliver high power outputs from several hundred MW up to 1000 MW and have large capacities of over 8 GWh. The following diagram illustrates the operating principle of pumped-storage hydroelectric plants.

Figure 3: Operating principle of a pumped-storage power plant (Source Voith Hydro (Voith (n.d)).

Figure 3: Operating principle of a pumped-storage power plant (Source Voith Hydro (Voith (n.d)).

Their overall efficiency reaches 80%. Pumped-storage hydroelectric plants can start up very quickly – maximum power is available in the grid in less than 5 minutes. Due to their long lifecycle, the cost per stored kilowatt-hour (kWh) is very low – between 2 and 3 cents/kWh. Pumped-storage power plants can also be built using conventional materials such as sand, cement, steel, and copper – these materials are available in large quantities.

Overall, German pumped-storage power plants currently have a storage capacity of around 38 GWh with a maximum output of 6.6 GW (Wikipedia (n.d)). To achieve the targeted storage capacity of 400 GWh by 2045, pumped-storage power plants would theoretically need to be expanded tenfold. Is this feasible in Germany? There is a prevailing impression that the necessary topographical conditions are not present in this country. However, this is not the case, but it does require an innovative approach.

The open-cast lignite mines in Germany offer ideal topography. While the open-cast mines in Lusatia and the Leipzig mining area are only about 80 m deep, those in the Rhineland reach depths of between 200 and 450 m. Consequently, a pumped-storage power plant for such open-cast mines must be designed differently to optimally utilize the available depth and size. One alternative would be the use of lower storage basins in the form of large hollow structures, for example made of concrete, at the bottom of the open-cast mine (Schmidt-Böcking et al., 2024; Luther & Schmidt-Böcking, 2023). A small area separated from the open-cast lake, which would later be flooded, could serve as the upper storage basin of a pumped-storage power plant.

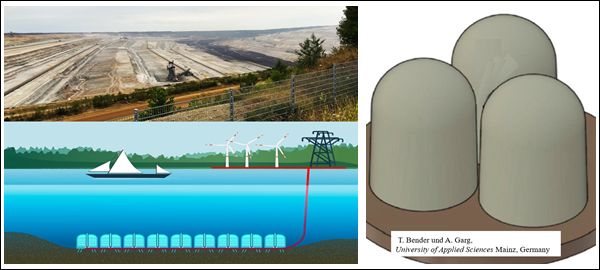

Figure 4 illustrates how the bell-shaped concrete caverns are constructed in the still-unflooded open-cast mine using sliding formwork, in which the formwork moves with the concrete structure. The dimensions of this bell-shaped cavern are shown on the right in Figure 4. The arrangement of the caverns on the open-cast mine floor is flexible.

Figure 4: Operating principle of a pumped storage power plant in open-cast mines – example Hambach open-cast mine (left image), example bell caverns (right image) (Schmidt-Böcking et al., 2024), (Luther & Schmidt-Böcking, 2023).

Figure 4: Operating principle of a pumped storage power plant in open-cast mines – example Hambach open-cast mine (left image), example bell caverns (right image) (Schmidt-Böcking et al., 2024), (Luther & Schmidt-Böcking, 2023).

Three bell-shaped caverns, each equipped with a pump turbine, form a unit with a total storage capacity of approximately 2.9 GWh at an average head difference of 360 m and an optimal efficiency of 80% per machine. A standard 350 MW pump turbine can store this amount of electricity in about eight hours and thus supply 300 MW to consumers for approximately eight hours. After flooding, the walls of the bell-shaped caverns must be approximately 4 m thick, with a maximum foundation depth of 400 m below surrounding area top upper edge, an inner diameter of 100 m, and a height of approximately 150 m (Garg & Bender, (n.d)). This size appears as a feasible maximum, for a 60 m diameter cavern static feasibility study was done.

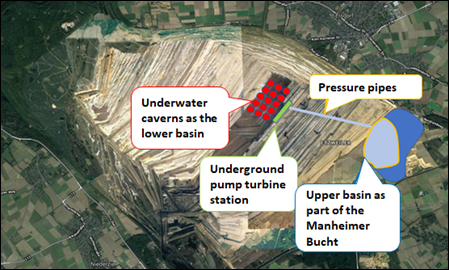

Figure 5 shows an example of a possible arrangement of the main components of a pumped-storage power plant. The caverns were constructed at the bottom of the open-pit mine. The upper reservoir can be built in a section of the Manheim Basin – a reservoir with an area of over 6 km², but only 10% of the maximum open-cast mine depth. The upper and lower reservoirs are connected by several penstocks; the power plant is located at the lower level near the caverns.

Figure 5: Possible arrangement of the elements of a pumped-storage power plant in the Hambach open-cast mine

Figure 5: Possible arrangement of the elements of a pumped-storage power plant in the Hambach open-cast mine

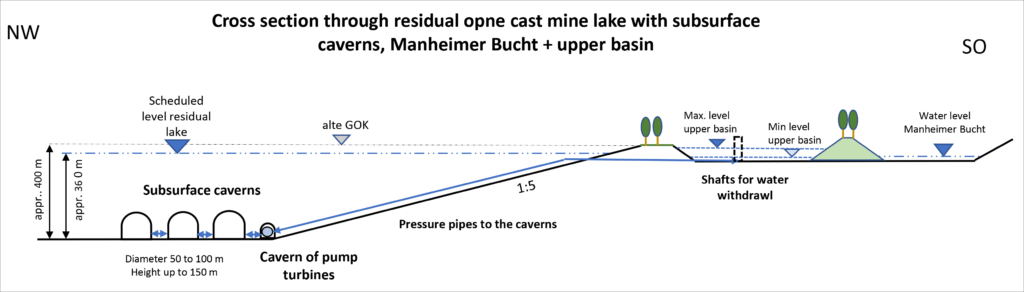

Figure 6 illustrates the distances and number of components of a pumped-storage power plant in cross-section. It shows also the very low depth of the upper reservoir compare to the rest of the open cast mine.

Figure 6: Cross-section of a possible pumped-storage power plant in the Hambach open-cast mine

Figure 6: Cross-section of a possible pumped-storage power plant in the Hambach open-cast mine

Figure 7 shows the situation in the Manheim Basin – a suitable area for the construction of the upper reservoir. The Manheim Basin has suitable geology – clay layers can serve as a natural seal for the upper reservoir.

Figure 7: View of the Manheim Basin (Manheimer Bucht) – in the current excavated area, potential location of the upper reservoir.

Figure 7: View of the Manheim Basin (Manheimer Bucht) – in the current excavated area, potential location of the upper reservoir.

The energy storage potential of such a pumped-storage power plant in an open-pit mine depends on the difference in elevation between the lower and upper reservoirs, as well as the available volume of water pumped by the turbines. This fluctuating water volume corresponds to the sum of the cavern volumes. With a cavern volume of approximately 1 million m³ per cavern, 60 caverns at the bottom of the open-pit mine, and a cycle length of 8 hours, a storage capacity of approximately 8 GW is possible in pumping mode and 6.6 GW in turbine mode. The available capacity in pumping mode is more than 50 GWh. This is significantly more than the total storage capacity of all other existing pumped-storage power plants in Germany of 38 GW in summary. This large amount can make a significant contribution to Germany’s energy transition.

The most important factors for economic viability are the investment costs, the operating cycles, the energy market framework, and the price difference between stored and drawn electricity (spread). Investment costs depend on construction costs, geology, logistics, grid connection, and the general economic situation. The number of operating cycles has increased significantly in recent years, from approximately 160 cycles per year to well over 200 cycles per year for pumped-storage power plants. This is due to the increased fluctuations between electricity generation from renewable energy sources and electricity demand. Current regulations favour battery storage systems, which are completely exempt from grid fees – pumped-storage power plants, however, are not! The price range is one of the most important factors – it has fluctuated considerably in recent years – but the average price has also increased. In summary, the economic conditions for pumped-storage power plants are improving.

Pumped-storage power plants are a proven and durable technology that can be implemented on a very large scale. They use almost exclusively locally available and non-critical materials. Large pumped-storage power plants in open-pit mines are ideally suited for balancing electricity demand between day and night after the fossil fuel baseload power plants are decommissioned over the next 10 years. These massive pumped-storage plants could make a significant contribution to solving the energy storage problem for all of Germany and, in part, for the EU as well. The large rotating masses of the turbines and generators contribute to grid stability (frequency and voltage) without the need for power electronics, thus reducing complexity. The installation of pumped hydro plants in mining areas which are devastated areas avoids the use of other landscapes. Cavern pumped-storage power plants form the third (almost forgotten) pillar of the German electricity storage concept. Large cavern pumped-storage power plants could also act as an economic stimulus program for the construction and mechanical engineering industries and offer potential for storage solutions, including in cooperation with the Netherlands and Belgium.

- Bundesnetzagentur, Datenarchiv SMARD, https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Home/_kacheln/ext_links/smard.html

- Bewertung Systemstabilitätsbericht Bundesnetzagentur (2025). https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Fachthemen/ElektrizitaetundGas/NEP/Strom/Systemstabilitaet/Bewertung2025.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

- Voith, (n.d). Pumpspeicherkraftwerke, https://www.voith.com/corp-de/branchen/wasserkraft/pumpspeicherkraftwerke.html

- Wikipedia, (n.d). List of pumped hydro power plants in Germany, https://t1p.de/WikiPump.

- Schmidt-Böcking, H., Luther, G., Duren, M., Puchta, M., Benderet, T., Garg, A., Ernst, B., & Frobeen, H. (2024). Renewable Electric Energy Storage Systems by Storage Spheres on the Seabed of Deep Lakes or Oceans. Energies, 17(1), 73. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3390/en17010073?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Luther, G., & Schmidt-Böcking, H. (2023). The role of short-term storage like hydropower in abandoned opencast mines in the energy transition, in: 791. WE-Heraeus-Seminar (2023) / The Physical, Chemical and Technological Aspects of the Fundamental Transition in Energy Supply from Fossil to Renewable Sources – Key Aspect: Energy Storage, Lecture 11.1, https://www.we-heraeus-stiftung.de/fileadmin/Redaktion/PDF/Seminare/2023/791_Booklet.pdf

- Garg, A., & Bender, T. (n.d). Hochschule Mainz, private notification

- Schmidt-Böcking, H., Luther, G., Lay, C., & Bard, J. (2013). Speicherung elektrischer Energie am Meeresboden. Physik in unserer Zeit, 44(4), 194 – 198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/piuz.201301330